The decline of the Moghul Empire and the corresponding rise of European civilizational constructs marks a watershed in the evolution of architecture in the Indian sub-continent.

Thinking critically about architectural production over these last two centuries requires a brave heart, in order to tolerate the loss - of principles, values and practices - of an architectural universe evolved over more than a couple of millennia. The few published accounts of the history of architecture in India provide a story of changes over time which only illuminates the surface of this art form. The academic view has obscured the inner being and spirit of this discipline which kept alive the art by allowing continuous renewal of the body. The body referred here is evident in the examples of beautiful and soul-stirring buildings from ancient times upto the Moghul period. What was the secret of this process of reincarnation?

Our belief in reincarnation is an ancient method for realizing the continuity of life forms and the essential interdependence of matter and energy. One can speculate that it was the understanding of this interdependence that gave our architecture a creative centre while illuminating the boundaries of our own nature to find expression in the world of form. If architecture can be likened to 'spirit', then building is the 'body'. The creation of a building is an activity integrating matter and energy in diverse ways and for a variety of purposes, but the essential understanding which guides this activity is the architecture, living on as the reincarnating spirit.

It is important today to remind ourselves of the essential relationship between materials and energy, since the last 2 or 3 centuries have seen this relationship being ignored and often fractured in the way we have used technology to shape our environment. Technological innovation has not been restrained by the limits of our capacity to tolerate change, resulting in the alarming degeneration of our physical environment and consequent threat to the survival of many living species, including humans in several parts of the planet.

There is a belief in ancient societies that the phenomenal universe we experience around us is duplicated within each human body. Our tools, therefore, while transforming the physical environment, simultaneously transform our inner selves. This places a responsibility on each one of us to select our tools with great care, evaluating the choice primarily in terms of life enhancement, rather than a mechanistic notion of efficiency or profit.

The act of building which gives life to architecture begins with the discovery of the site as a matrix for integrating land and human activity, proceeds with transformations of materials and energy flows, resulting in a re-creation of the elements in a form which enhances nature. These essential relationships emerge from the creation of an appropriate architectural proposition which integrates 'thinking' and 'making', so that the building becomes a container of life even as its construction and maintenance becomes a life-enhancing activity.

The theoretical construct outlined above can be best illustrated by a worked example. The case chosen here is a building constructed in 2000 CE on the south-western edge of New Delhi.

LAND

The land here is part of the Aravalli range, and at the start of construction had an uncultivated and ancient presence.

SITE

The site was contained by a rubble stone wall set on slightly sloping ground , and it was part of a cooperative' subdivision of a one hectare farm in a rapidly urbanizing village originally settled by gujjars and adivasis. There was minimum urban infrastructure, a kuccha access road, a temporary single-phase electric supply, and a telephone line. Water was made available from a deep tube-well in the compound. The building, therefore, had to rely largely on the resources of nature for its life-support system.

MATRIX FOR INTEGRATING LAND AND HUMAN ACTIVITY

The building was to house a couple, an architect and his wife, with visiting children and elderly relations, as well as serve as the architects studio. Their share of the land was 450 square meters. There was an understanding within the cooperative that the subdivisions would not be separated by compound walls and that the built structures would be ecologically viable.

The spatial geometry created minimum built area with taller volumes, and the accommodation requirements were reduced to the essentials, so that the built area of the residence was contained in 170 square meters and the studio in 100 square meters.

TRANSFORMATION OF MATERIAL AND ENERGY FLOW

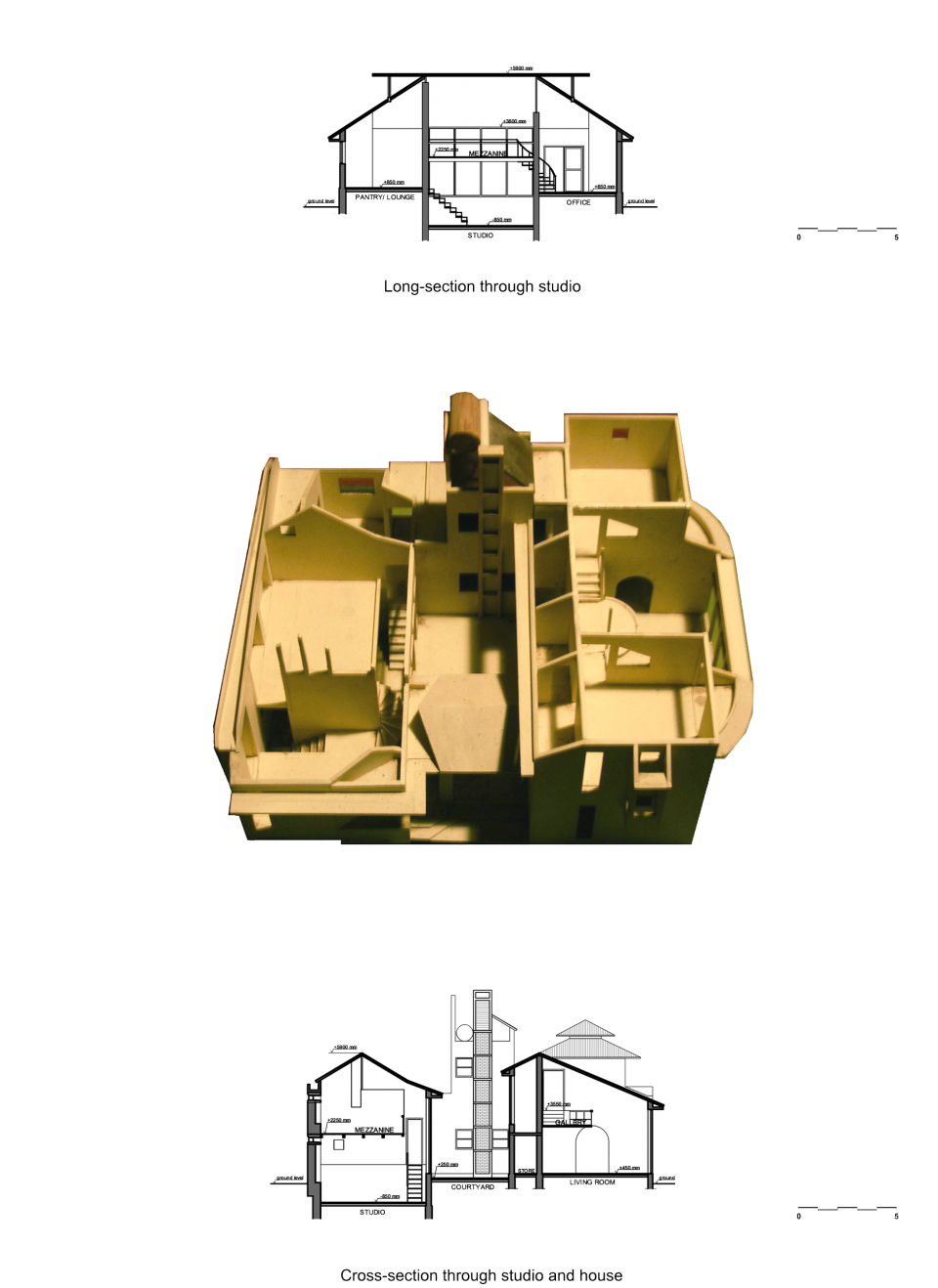

As a result the design emerged as a low-rise building with sloping roofs to regulate solar heat gain, and to provide shelter from the rain with a low embodied-energy material like clay tiles for roofing. The sloping roofs also allowed the insertion of mezzanine floors without making the building too tall; providing a gallery overlooking the living area of the residence, and a loft for a conference area in the studio.

The roof of the studio enclosed a singular volume, thereby becoming a metaphor for a 'shed', having four discrete working spaces visually separate but clearly interconnected parts of the single volume.

roof of the residence emerged as a collection of tower-like peaks and sloping surfaces, serving as metaphor for 'palace', to contain a variety of domestic requirements like bedrooms, bathrooms, closets, sitting and dining areas, kitchen and utility spaces, as well as a backyard and a garden to extend the living areas.

The two parts of the building, for home and studio, are connected by an entrance verandah directly approached from the public driveway, and separated by an open-to-sky courtyard off this verandah.

The internal courtyard brings natural light and ventilation into the studio which is built against the northern compound wall of the property, thereby increasing the area of the south-side garden for the residence.

SPATIAL ORDER

The plan form is ordered by a series of service spaces, like staircases, bathrooms, closets, and utility spaces grouped around the internal courtyard which forms the centre of the built environment. Placed in the centre of the courtyard is a metaphorical Mount Meru, which also serves as a stand for growing a tulsi plant. This metaphorical navel is set within a spiral channel to direct rain water in the courtyard, and it has embedded in its surface another spiral, turning in the opposite direction, to direct the overflow of the water used to keep the tulsi plant wet. The courtyard forms the entrance foyer to both the house and the studio, and is sheltered from the public driveway by a perforated mild steel screen wall with two gates, one for home and the other for studio.

The perforated metal screen is decorated with the archetypal 'tree of life' rendered in mild steel flat, which also helps to reinforce the structure of the screen and gates. All habitable spaces are oriented to gave major openings on south facing walls to allow the winter sun, low in the southern sky in Delhi, to penetrate indoors and maximize solar heat gain; while the summer sun, high in the sky, does not enter any of the rooms thereby minimizing adverse heat gain.

Bedrooms on the upper floor have a pyramidal roof form with a ventilating monitor at the peak, which allows hot air to exhaust naturally and maintain thermal comfort in summer. In winter the monitor ventilation is closed by a set of trapdoors.

RECREATION OF THE ELEMENTS

The external walls are load-bearing brickwork laid in rat-trap bond to improve insulation, both thermal and acoustic, through the simple expedient of an air gap between two skins. Embodied energy in the building fabric is kept low by minimizing the use of reinforced concrete, using r.c. filler slabs for the intermediate floors of bedrooms, with compressed earth blocks, made on site, for the filler material. The mezzanine floors are sawn hardwood (shisham) planks supported on mild steel structural hollow section framework. This kind of mild steel framework is also used for supporting the roof, taking advantage of its beneficial weight-to-span ratio for structural efficiency and energy-saving.

The land being uncultivated for a long time, its soil was infested by termites. Door and window frames were consequently made of sandstone, by craftsmen from nearby Rajasthan where sandstone has been traditionally used for this purpose. Details of the frames were worked out afresh to accommodate contemporary patterns of use and available hardware. Door shutters and ventilators fitted in the stone frames were crafted from "shisham' wood with infill panels of bamboo ply. Cabinets in the kitchen and dining room, as well as the book shelves in the sitting room were made of 'kail' wood, softer and easier to work with than, 'shisham'. Flooring in the living areas and bedrooms was chosen as terracotta tiles, being a maintainable earthen finish, cool in the summer and warm in winter.

A multipurpose bracket was specially designed, to be crafted out of ' shisham' wood, and to serve as a wall and ceiling lamp holder, for fixing curtain rods, staircase handrails, as well as towel rods.

REINFORCING ECOLOGICAL CYCLES

There was no municipal provision for drainage or sewage. It was agreed between the members of the cooperative subdivision that the waste water and rain water would not leave the compound but be suitably treated and harvested to recharge ground water resources. For sewage treatment a linear reed bed was constructed along the two open boundaries of the building plot, discharging the treated effluent into a one meter diameter by three meter deep soakage well below an inspection chamber. The house under discussion and the neighboring house were both connected to the reed bed. The treated effluent passing through the inspection chamber was regularly checked for its qua1ity, which was found to be without any turbidity or odour and quite suitable for irrigation purpose. The reeds quickly grew to a height of two to three meters and provided an effective boundary screen for the house and garden. The trees and other plants growing near the reed bed flourished and became luxuriant.

AESTHETIC OF THE ESSENTIAL

The idea of economy of means and maintaining energy balance was the guiding principle of design and construction at all scales, from the small detail to the large environmental order, thus creating an aesthetic of the essential. The architecture then becomes a schema for understanding and appreciating the continuity of life-forms by the integration of energy and matter. The act of building, informed by the same awareness of survival across time, makes a seamless connection with philosophical intent, making the built environment a repository of life as culture which maintains its intensity and validity across time and space. If such inspiration fires the creative urge, it is conceivable that architecture is able to represent paradise and embody universal form. Architecture can therefore be the reincarnating spirit which integrates space and matter, form and function, philosophical intent and constructional method, to provide us with a built environment which makes us aware of the continuity of all life forms and the wholeness of our being.