HAVING discussed the general characteristics of Muhammadan buildings in the first three centuries of their domination in Northern India, I think it will help to explain more fully the previous chapters as well as those which follow if we begin now to analyse the evolution of various important details in Indian architecture, both as regards structure and symbolism. In Indian art the ideal and the practical act and react upon each other to such an extent that it is impossible for the outsider to understand fully the one without knowing the other; for if in the primitive stages of constructive development we shall find the symbolism growing out of practical craftsmanship, we shall discover later that the symbolism itself often leads to constructive ideas.

We have before noticed that the pointed arch was by no means unfamiliar to Indian craftsmen before the Muhammadan invasion, though structurally they had used it very sparingly and on a small scale. It has not yet been understood by European writers that the trefoil arch originated in Indian Buddhist symbolism many centuries before it appeared in Western art. In India, as in Europe, it was a form which architecture borrowed from the graphic arts, for it originated with the transcendental ideas connected with the Indian conception of the Deity, and with anthropomorphic symbolism. As far as we know, the various forms of Indian religious ritual which were directly derived from Aryan teaching had this in common with Muhammad’s creed, namely, that until the beginning of the Christian era they discountenanced any representation of the Deity in human form. In early Buddhist sculpture the symbols of worship are inanimate memorials of the Master’s life on earth; the Bodhi tree underneath which he won Nirvana1; his sacred footprints; his begging bowl; but not his own person. Whether Buddhists until the time of Nâgârjuna had the same feelings as Muhammadans regarding the representation of the Deity, or whether it was simply that they had not until that time regarded the Buddha as a divine being, I will not attempt to discuss. The important point in Indian architectural history is that the various forms of foliated arches were associated with the first painted and sculptured representations of the divine Buddha, which began to appear with the rapid spread of Mahâyâna Buddhism in the early centuries of the Christian era.

It has been supposed by Oriental scholars that the earliest sculptures of this kind are those of Græco-Roman craftsmen of the Gandhâra and Mathurâ schools; but I believe that further archæological investigation will show that this assumption is untenable. Sister Nivedita has drawn attention2 to internal evidence in the Gandhâra sculptures which seems to indicate that they are only Græco-Roman reproductions or imitations of a pre-existing Indian model of the divine Buddha which should be sought for in the Magadha country. It is possible, again, that Indian Buddhist sculptors were borrowing from earlier Jain representations of their quasi-divine teachers, the Tirthankaras. In any case the symbolism or the ideal from which the trefoil arch is derived was not Greek, or Roman, or Saracenic, but purely Indian.

The trefoil was the shape of the aura, the glory or divine light which shone from the body of the Buddha from the moment when he attained Nirvana under the Bodhi tree at Gayâ. The simplest form of the aura, as drawn by painters and sculptors—and probably the earliest—was the lotus-leaf shape, derived from the gables and windows of the barrel-vaulted roofs of early Indian buildings, which again might have had their prototype in the primitive structures of reeds and thatch which are still found in Mesopotamia.3

The term “horse-shoe” arch as applied to these Indian Buddhist buildings by Fergusson and other writers is very inappropriate, for the horse-shoe has no meaning in such a connection, whereas the lotus leaf was a symbol so full of sacred associations for Buddhists that this form of window and gable is found constantly repeated in early Indian buildings as a decorative motif when it was not required structurally. The idea of good luck popularly associated with the horse-shoe is perhaps derived from its resemblance to the lotus leaf. The outer curve of the lotus-leaf arch (Plate XXIX, fig. A) took the form of the leaf of the sacred pîpal—the Bodhi tree (fig. 14).

The pîpal tree was associated with the enlightenment of Buddha; but various trees, such as the banyan, were dedicated to other religious teachers, the favourite place for a yogin’s meditation being under the shade of a tree. When a Rishi was worshipped as a deity, it was therefore appropriate to make the aureole round the head of the image take the shape of the leaf of his especial tree; by an easy transition of ideas the leaf was transformed into a flame.

When used to represent the aura in a sculptured or painted figure of Buddha, the lotus leaf was generally associated with the makara, a kind of fish-dragon, the fish being an emblem of Kâma, the god of love, and of fertility (Pl. XXIX, fig. B): here points of flame are added to the edge of the lotus leaf. The fish was also a sign of good luck, for in the Indian legend of Creation it was a fish that saved Manu, the progenitor of the human race, from the flood. This form of aureole with the makara and lotus leaf combined is still a tradition with Saivaite image makers in Southern India.

The trefoil arch was a compound aureole, or nimbus, made up of a combination of the lotus and pîpal or banyan leaf slightly different to that which obtained in the window or gable described above. The pîpal leaf stood for the glory round the head of the Buddha, while the lotus leaf remained as before to indicate the shape of the aura which surrounded the body. The intersection of the two formed the trefoil arch with a pointed crown (Plate XXIX, fig. C). A very common variety of this was made by the chakra, or wheel of the Law—which was also the emblem of the sun-gods, Vishnu, Sûrya, and Mitra—taking the place of the pîpal leaf, making the crown of the arch round instead of pointed.

The structural use of these trefoil arches and of their derivations began in Indian buildings about the same time as the painted and sculptured representations of the Buddha were introduced into Indian art—i.e. in the early centuries of the Christian era, when images were placed in niches in the walls of temples, monasteries, or relic shrines, the niche itself taking the form of the aureole. A common form of the niche was the lotus-leaf gable with the pîpal-leaf finial (Pl. XXIX, fig. D).

A Græco-Roman adaptation of this with trefoiled arches—showing the round aureole of the cult of Mitra combined with the pointed pîpal leaf of Buddhism—is given in Pl. XXX, A, taken from the ’Alî Masjid stûpa in the Gandhâra country, a building of about the first century A.D. Several varieties of arched niches of a date long anterior to the Hegira are found in the ruins of the famous Buddhist monastery of Nâlanda (Plate XXX, B), which flourished from the early days of Buddhism until about the eighth century A.D.

The sun-temple of Mârtând in Kashmir, built in the middle of the eighth century, shows the round trefoil arch used structurally both for doorways and for niches (fig. 16): this being a stone building, the usual Indian method of constructing arches in horizontal courses is used here, as it was several centuries later in the arched screens of the mosques at Old Delhi and at Ajmîr. The transition from the simple lotus leaf, or so-called horse-shoe arch, to lobed or cusped arches was all the more easy because the inner curve of the early Indian gable or window was divided into a number of equal spaces by the ends of the horizontal wooden purlins which supported the roof (see Pl. XXIX, fig. A). When an image with the wheel nimbus behind the head was placed in one of these gable niches, it would be an obvious elaboration of the niche to continue the half-wheel all round the latter so as to produce the cusped arch shown in fig. C, which is a form of bracket commonly used in Hindu temples of Western India for distributing the weight of the heavy architraves between the columns (Pl. XXX, C). The makara or fish emblem at the springing of the arch shows the derivation of this bracket form from the aureole of images. This bracket, again, was the prototype of the lobed or cusped arches in later Muhammadan buildings. It is used for its original purpose as a bracket in the Jâmi’ Masjid at Ahmâdabâd (Pl. XXV).

The Buddhist or Vaishnavaite wheel or half-wheel was also a very common decorative motif in ceilings and in the interior of Indian temple domes. The wheel is even found crowning the pinnacle of Saracenic mosques, and it is from the half-wheel, rather than from the Roman scallop, that both Saracenic and Gothic cuspings should be derived, for the examples of sixth and eighth-century cuspings given by Professor Lethaby4 as prototypes of the Gothic should, I think, be recognised as vestiges of the Buddhist influence in Western Asia rather than of the Roman.

The arched niches for images which were so numerous in early Buddhist buildings in India, and from India passed into Western Asia with Buddhism, were superseded in later Indian buildings, constructed chiefly of stone, by rectangular niches, not because the symbolism of the aura fell into disuse as Buddhism declined, but because the aura was elaborated ornamentally to such an extent in later Buddhist, Jain, and Brahmanical iconography that it became a part of the sculptor’s rather than the builder’s craft, and in stonework was usually carved out of the same block as the image to which it belonged.

Thus every conceivable variety of pointed and round arches, with or without cuspings, were familiar to all Indian craftsmen for centuries before the Muhammadan invasion, though they were generally recognised as belonging to the design of metal and stone images.

Now, when Muhammadan ritual insisted that arches should be used in Indian mosques, the first impulse of the Indian craftsmen was to adapt these plastic forms, with which they had been familiar for centuries, to structural purposes. They proceeded to Indianise the Persian or Arabian type of pointed arch, originally derived from early Buddhist shrines, first by giving the crown the pointed tip of the pîpal leaf, like the aura of Indian Buddhist images. This we can see in a great many of the thirteenthand fourteenth-century Indian mosques the first one at Old Delhi, the next at Ajmîr, and several of those at Jaunpur, Ahmadabad, and Mandû. At first it was done tentatively and somewhat crudely, with the effect of weakening the appearance of the arch, though it tells unmistakably that Indian and not foreign masons were at work. The Indian craftsmen themselves evidently saw that the arches thus partially Indianised were not æsthetically satisfactory, for already in Altamsh’s mosque at Ajmîr they began to foliate them (Plate X).

Another device used in India in Muhammadan buildings, for relieving what seemed to the Indian craftsman’s eye the monotonous line of the Saracenic arch, was an enrichment of the soffit of the arch with a characteristic Indian ornament, used experimentally in many of the earlier buildings and developing later on into the more elegant form of it seen in fig. 17, which is from one of Akbar’s buildings at Fatehpur-Sîkrî (sixteenth century).

But while, on the one hand, there was a tendency in early Muhammadan buildings in India to elaborate upon the little that can be called Saracenic, there was, on the other hand, a marked endeavour to reduce to the simplest form of expression the major part which was Buddhist or Hindu. It was almost as if the Indian craftsmen, under the influence of Islâm, were reverting to the style of early Buddhist art. The masonry and sculpture of the Muhammadan mosques at Gaur are especially interesting for showing the transition of medieval Buddhist-Hindu forms of structure and decoration into the simplified aniconic types which they assumed in Muhammadan buildings. The architraves of the two doorways of the Chota Sonâ Masjid (early sixteenth century) shown in Plate XXXI are clearly derived from Hindu prototypes similar to those which were used by the Gujerat builders as models for a mihrâb (Plate XXXII), though in this case all the details are simplified, all anthropomorphic symbolism is studiously avoided, and the sculpture is kept in very low relief. Thecusped arches of the heads of the doorways are of the same type as those which are used in the more famous Mogul buildings of the seventeenth century, such as the Diwân-i-Khâs at Delhi and the Motî Masjid at Agra. They are obviously only a simplification of the highly ornate foliated brackets, derived from the Buddhist half-wheel as explained above, such as we see in the porch of the Mudherâ temple (Pl. XXX, fig. C). The ogee curve at the springing of the arch—which distinguishes most Indian foliated arches from Saracenic—is the simplified profile of the makara, or fish-dragon emblem, which belongs to the Buddhist-Hindu prototype.5

The masonry of the heads of the two doorways shows the transition from the bracket to the arch. In the right-hand doorway (B) the mason has constructed the head of it in Hindu fashion as a bracket pure and simple; using only four blocks of stone, but inserting a small oblong piece above the crown of the false arch, apparently on account of a fault in the two larger blocks, or to correct some mistake in the carving. In the other doorway (A) of the same design the blocks are cut as in the true arch, and a keystone is inserted, probably because the mason had not stone of sufficient size to complete the arch with four blocks, like the other. It will be noticed how frequently the open lotus flower, the sun-emblem, is used as an ornament—a reminiscence of the early Buddhist rails.

The beautiful mihrâb of the fourteenth-century Âdînah mosque at Gaur (Pl. XXXIII) is so obviously Hindu in design hardly to require comment. One only has to search among as the ancient sculptures which are scattered in profusion about the districts surrounding Gaur to find any number of its Hindu or Buddhist prototypes. The image of Vishnu or Sûrya found lying near a village in the Manbhum district of Bengal has a trefoil arched canopy, symbolising the aura of the god, of exactly the same type as the outer arch of the mihrâb, only the sculptor of the latter has studiously observed the Muhammadan law in converting the rakshasa’s or demon’s head which Hindu tradition placed at the crown of the arch, and all other symbolic ornament derived from animate natural forms into conventional foliage. Except for the absence of such symbols and of the image in the niche, the whole mihrâb is completely Hindu, both in construction and in design.

The only suggestion of Saracenic influence is in the inscriptions and arabesque ornament with which the whole of the plane surfaces of the wall are covered. The technical treatment of these, as a kind of fretwork in two planes of relief, was derived from the Arabian practice of carving quotations from the Qurân on the walls of their mosques. For the sake of clearness the inscriptions had to be treated in this way, without any plastic elaboration, and when they were finished the inventive imagination of the carvers took delight in covering the rest of the surface with geometric and foliated patterns of infinite variety, kept flat like the inscriptions. This was the Musulmân craftsman’s substitute for the wider and more human field of interest in which the Hindu sculptor revelled. If the former was less liable to run into extravagance, it was because his range of expression was much more limited; not because his artistic capacity was greater: though it may be that the greater reticence imposed upon him by this limitation was sometimes a useful discipline for the Oriental imagination.

If the various stages in the evolution of the arch in India are carefully studied, it will not be difficult to trace the Buddhist-Hindu craft tradition in the later Muhammadan buildings which Fergusson and other writers wrongly classify as “Saracenic.” Take, for example, the fine recessed doorway of the ’Ali Shâhi Pir-ki Masjid at Bijâpur (Plate XXXV).

The Bijâpûr buildings are justly commended by Fergusson for their originality, largeness, and grandeur, but as usual he tries to find an explanation for these qualities in the fact that the Âdil Shâhi dynasty under which they were constructed was of foreign (Turkish) descent, and hated everything Hindu. A careful examination of the doorway in the light of the explanation given above will prove that the whole design of it bears not a trace of foreign inspiration; like the vast majority of Muhammadan buildings in India, it shows only a skilful rearrangement of traditional Hindu constructive and decorative ideas within the limitations imposed by the law of Islam. All the arches have the pîpal-leaf crown. The bracketing under the front arch is unmistakably Hindu, likewise the cusped ornamental arch which goes round it. The conventional device at the crown of the cusping is the Muhammadan aniconic rendering of the Hindu rakshasa’s head (kirtti-mukhi). The circular ornaments in the spandrils of the arch are flattened-out lotus sun-emblems, which are so conspicuous in the rails of Buddhist stûpas, in Muhammadan disguise. We have seen them already (Pl. XXXI) in an early sixteenth-century mosque at Gaur in their original Indian form. Another very common Hindu motif is the amalaka ornament which fills in the angle between the two inner arches. The structural basis of the whole doorway can be seen in the buildings of the Muhammadan quarter in the neighbouring Hindu city Vijayanagar (fig. 43).

A very characteristic feature of Indian architectural design from the fourteenth century onwards was the combination of the arch with the bracket; the bracket generally playing the constructive part in accordance with Hindu tradition, the arch being used as a symbolic and decorative element. We shall find this combination very frequent in the sixteenth-century Mogul buildings of Akbar’s time. The interior of Ibrâhîm’s tomb at Bijâpur (Plate LXXXV) also illustrates it.

The bracket by itself was of course one of the distinctive features of Hindu building construction before Muhammadan times. It would require a lengthy monograph to illustrate all its constructive applications, and to do justice to the infinite skill and fancy which the Indian craftsmen lavished upon the carving of their brackets. The noble gateway at Dabhoi (Plate II) makes one understand the reluctance of Indian builders to use the arch, even for wide openings, when they had plenty of fine material for brackets like these to support the lintels.

The Muhammadans continued to use the bracket throughout most of their buildings, but added nothing to the Hindu craftsman’s knowledge in this respect. Their smaller arches were very commonly formed of two brackets joined together. The true arch was generally reserved for wide openings which could not be easily spanned by beam and bracket. The deep bracketed cornices, or dripstones, as well as the balconies supported on brackets, which are so frequent in Indian Muhammadan buildings, are of pure Hindu design without any Saracenic suggestion.

We will now pass on to consider the construction and symbolism of Indian domes, as found in Muhammadan buildings. Though the dome seems to be so distinctively characteristic of Saracenic architecture, there is not, pace Fergusson, a single type of dome in Indian Muhammadan buildings which is not of indigenous origin or derived from early Buddhist prototypes.

It is the case in all countries, but more especially in India, that the great architectural monuments now extant, which seem to us to exhaust all the possibilities of ancient art and science, represent only a very srnall number of the links in the development of building methods. The missing links are, however, frequently to be found in the humbler dwellings built by craftsmen of the present day who have inherited the traditions of ancient times. In India a few pictorial fragments or rock sculptures are all the indications we now have of many centuries of architectural growth and of thousands of magnificent buildings which in the days of powerful Buddhist and Hindu dynasties were mostly constructed of wood, brick, and plaster—materials which have comparatively little permanence in a tropical climate and offer little resistance to the destructive energies of foreign invaders or the fury of iconoclasts. But the living traditions of Indian craft, the study of which has been so much neglected, will often supply clues for which the archæologist searches in vain among the monuments of the past.

There are two methods of domical construction found in early Muhammadan mosques in India—one, peculiar to India, in which the dome is built up of horizontal courses of stone; the other in which stone ribs resting upon the octagonal base form the structural framework, the intervals between the ribs being filled up with horizontal masonry. The reconstructed Hindu domes used in the Qutb Mosque (Plate IX) are examples of the first method. The dome of the Champanîr Jâmi’ Masjid (Plate L) is an illustration of the other.

Fergusson made a cardinal mistake in supposing that the latter method was not an Indian one.6 Not only was it Indian but the ribbed dome was certainly the earlier of the two Indian types; for the method of construction is directly derived from primitive or temporary domes built with a framework of bambu or of wood, whereas the alternative method is distinctly lithic in its technique.

The principal Indian building styles may be roughly divided into three main periods according to roof construction, which is the chief determining factor in the evolution of architectural style. The first period is that in which roofs are built with a framework of bambu; in the second period the bambu construction is reproduced more permanently in timber carpentry; in the third period the wooden construction is adapted to brick or stone. In all three periods brick and stone were used to some extent in the substructure of the buildings. The same classification will serve to indicate roughly the buildings which belong to three different strata of society—the first one representing the humble dwellings of the ryot and of the lower castes generally; the second the houses of the well-to-do middle classes; the third, the palace of the rajah and of the nobility, state buildings, military or civil, and temples or mosques.

The vaulted roofs of Asokan buildings, as sculptured in the Bharut and Sânchî reliefs, are all derived from bambu prototypes. The style we see here, which might be called the Early Magadhan style, belongs to Bengal, a country in which the bambu even in the present day determines the structural character of village huts and also that of temple architecture.

The modern Bengali style of temple, so far from belonging to what Fergusson calls an “aberrant type,” is the lineal descendant of the early Magadhan style. The form of the lotus-leaf or “horse-shoe” window or gable of the Asokan buildings is that which bent cane or bambu naturally assumes. The elasticity of the latter is a valuable quality in roof construction which Bengali craftsmen were not slow to utilise; but there were ritualistic as well as technical reasons which commended this form to the Asokan builders. The lotus-leaf arch symbolised the sun rising from the sea, or from the banks of the holy Ganges. The adoration of the rising sun has been from time immemorial, and still is, an essential part of all Indian religious ritual, and it agreed well with the joyous spirit of the early Buddhists to let the sun’s first rays enter into their houses and shine upon the images in their temples through these lotus-leaf windows and gables. Their vaulted roofs were first built in bambu ribs of the same form; in the rock-hewn Buddhist chapter-houses of a later period we can see the bambu ribs imitated in wood (Plate I). When stone began to be used more extensively in building roofs, the difficulty of making, such stone ribs for vaults of large size probably led to the trabeate style of building, with terraced roofs, taking the place of the early Magadhan method, except in the country of its origin, Bengal, where brick vaulting and arches came into use.

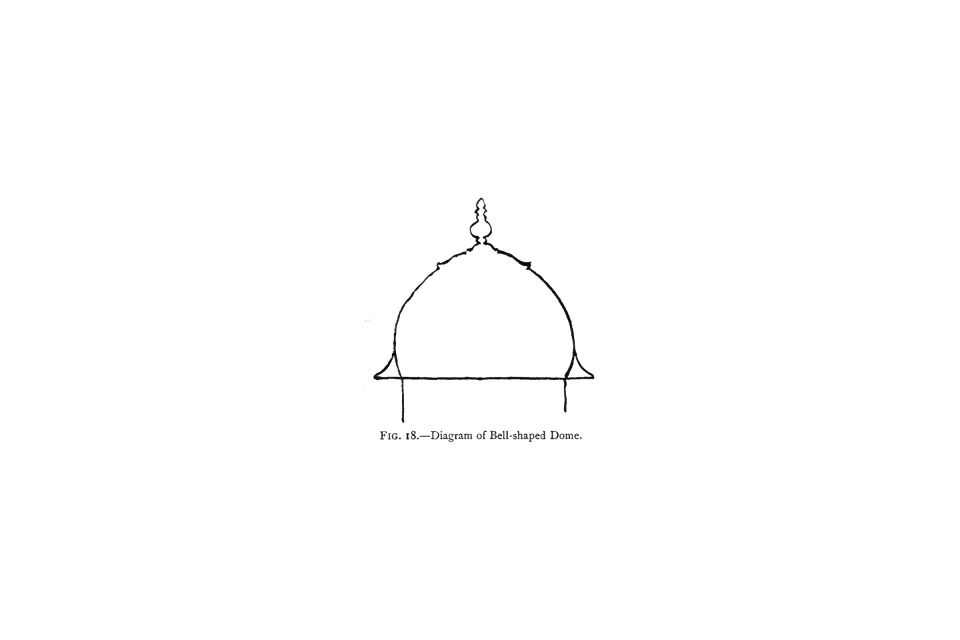

The principle of ribbed dome construction continued, however, to be used for domes not built solidly of stone or brick. The lotus-leaf or bent-bambu arch became the structural basis of the dome, known to Western writers as the “bulbous” or “Tartar” dome. The earliest Indian domes—those of stûpas or relic shrines—were approximately hemispherical in shape and built of solid brickwork; but when images of Buddha began to be placed under domed canopies supported by columns, such as we see sculptured on the façade of the great Ajantâ chapter-house (Pl. VI), the dome was necessarily a structural one, and, being so, would be constructed in the Magadha country with ribs of bambu bent into the lotus-leaf or “bulbous” shape. The eight-ribbed Dravidian domes, such as are sculptured at Mâmallapuran and Kalugumalai (Pl. XXXVI), are all reproductions of structural domes of this type built with bambu or wooden ribs; the bell-shaped dome being derived from the lotus or bulbous dome by adding eaves with an upward curve (fig. 18), which served the practical purpose of keeping the rain off the walls of the building.

The symbolism which the ancient Hindu craft canons—the Silpa-sâstras—connects with the ornamentation of a dome7 is directly derived from the principles of bambu or wooden construction. The ornament gave symbolic expression to the most vital parts of it. In a primitive ribbed dome, made with a bambu or wooden framework, there are four essential parts which ensure the stability of the whole (fig. 19): (1) the pole or axis, which must be firmly fixed either in the ground or upon a stable base, such as an inner roof or dome; (2) the bambu or wooden ribs; (3) the ties by which the ribs are secured to the pole at the springing of the dome; (4) the cap which secures them firmly at the crown of the dome.

The lotus petals which invariably decorate the springing of an Indian dome are placed just where the ties—forming a chakra, the wheel of the Law to Buddhists and a symbol of the universe to all Hindus—bind the ribs together at the base. The eight spokes of the wheel would be placed auspiciously by the master-craftsman in the direction of the four quarters and four intermediate points. The cap at the crown of the dome—decorated by the Mahâ-padma, the mystic eight-petalled lotus, or by the amalaka—resembled the nave of a wheel, the most sacred of symbols as denoting the central force of the universe, the Cause of all existence. Hence the prominence which was given to this member by all Indian craftsmen, and the veneration with which the amalaka was regarded. The water-pot or kalasha, containing a lotus bud, placed above the Mahâ-padma or the amalaka as a finial was a most appropriate symbol of the creative element and of life itself.

The primitive lotus dome, translated into permanent materials (fig. 20), had many practical recommendations, for the form is one in which the outward thrust is reduced to a minimum. Hence, although in India, when stone began to be largely used in temple building, the system of building massive domes in horizontal courses largely superseded the Buddhist method, the earlier system used by Indian craftsmen continued in vogue in Persia and Central Asia, where stone construction on a large scale never became general.

The tomb of Timûr at Samarkand (1405), in which Indian craftsmen assisted, was built on this early Indian principle, with internal ties in the shape of a wheel fixed to the central axis which is supported upon an inner dome.8 This is precisely the method by which the domed canopies of the Indian Buddhists shown on Plate VI must have been constructed, when built of concrete or of brick. In this case the inner dome takes the place of the principal wheel and acts as a support to the subsidiary one above it. The same methods are used in modern Persian domes,9 which, like the early Indian structural domes, are always built of light materials.

The construction of the Indian dome with the wheel and ribs explains the origin of the foliated devices, somewhat similar to the stalactite vaulting of the Saracens, and still more suggestive of the Roman scallop, which are so often used in the internal decoration of domes and ceilings, both in Hindu temples and Muhammadan mosques.

The whole design (Plate XXXVII) represents the open lotus flower. The circles and semi-circles arranged in foliated patterns which are units of the decoration have nothing to do with the Roman scallop: they are eight-ribbed Indian domes and half-domes in miniature (seen from the inside) cut into the masonry to reduce the weight of it. Each miniature dome also represents a lotus flower enclosed in the wheel (chakra) of Vishnu.10

Fig. A, Pl. XXXVII, shows the interior of one of the domes of Qutbu-d-Dîn’s mosque at Old Delhi, constructed from the material of Hindu temples roughly pieced together. Fig. B in the same plate shows the plan and section of the dome of a Hindu temple at Sunak, in Gujerat, which Dr. Burgess attributes to the tenth century A.D. It is interesting as an example of the transition from the earlier wooden structural methods of the Buddhists to the lithic methods of the Hindus, for here the ribs are reduced to mere ornaments, sculptured with mythological figures, which serve no structural purpose.

I have already shown how the bell-shaped dome was derived from the lotus dome. The bell, as one of the symbols of vibration, the cosmic creative force, played as important a part in early Buddhist ritual as it does in Hindu ritual of the present day. The bell-shaped fruit of the sacred lotus (Nelumbium speciosium) (fig. 21) had been from time immemorial a traditional motif for the capitals of Indian temple pillars: the torus (a) beneath the seed-capsule to which the petals of the flower are attached formed a strongly emphasised moulding in the design of the capital; and lotus petals were generally used to decorate the surface of the upper member, which corresponded to the seed-capsule of the real lotus.

The transition from the lotus dome to the bell-shaped dome was thus an easy one for the Indian craftsman to make, whether the starting-point was structural or symbolic. The bell-shaped dome became the usual one for Buddhist stûpas and temples; but in order that it might be visible from a greater distance, the height of the bell in proportion to the base was gradually increased. These elongated bell-shaped domes, which are characteristic of Burmese and Siamese architecture, were built of solid brickwork in the more important Buddhist buildings; but the ribbed principle of construction remained in the Indian craft tradition, for it must have been followed in all the temporary or less important structures built of wood or bambu.

Now when the same kind of structure was made by Indian stonemasons, it became structurally convenient to simplify the form by leaving out four of the eight ribs, and thus the curvilinear spire, the so-called “sikhara” of northern Hindu temples, was evolved from the Buddhist bell-shaped dâgaba or stûpa. This has long been a puzzling problem to archæologists, though from a craftsman’s point of view the solution of it seems simple. Fergusson only surmised that the sikhara was “invented” principally for æsthetic purposes. Several other archæological writers have connected the sikhara with the Buddhist stûpa without explaining the process of its structural evolution—i.e. that it is a four-ribbed, bell-shaped dome of abnormal height in proportion to the base.

As in the case of the “horse-shoe” arch, the archæological name given to this spire, or dome, is inappropriate. The modern temple craftsman in Orissa, where the Indian Buddhist traditions are still alive, knows it not as a sikhara (a pinnacle or spire), but as a gandhi (a bell), a name which connects it definitely with the Buddhist bell-shaped dome.

Pl. XXXVIII, a ruined Hindu temple at Khâjuraho, shows the ribbed construction of the sikhara or gandhi. The structural modifications of the original wooden prototype which are found in stone-built sikharas are only those which the change of material made necessary. It was impossible to make continuous stone ribs of the length required, so it became usual to build them up in small stone vertebrae, like the human spine. The stability of the structure was secured by building it up in several stories, with through courses of masonry between each. The transition from an octagonal or polygonal sikhara to a four-ribbed one is sometimes to be seen in two adjacent temples (Pl. XXXIX). The amalaka which crowned the sikhara performed structural functions similar to those of the cap, or Mahâ-padma, of the lotus dome.

From these considerations it will be clear that Indian masons, when they were employed by their Muhammadan rulers to build domes of greater size than was usual for them, needed no foreign architects to teach them the construction of ribbed domes—it was part of their ancient craft tradition. For understanding the development of Muhammadan architecture in India it is very necessary to realise that many of the forms which Western writers describe as “Saracenic” in Persia, Arabia, and in Egypt were Buddhist and Hindu long before they became Saracenic; so that the Persian influence which flowed into India with the founding of the Mogul Empire was largely a return wave of the Buddhist influences which spread from India into Western Asia, and far beyond, centuries before the Muhammadan supremacy.

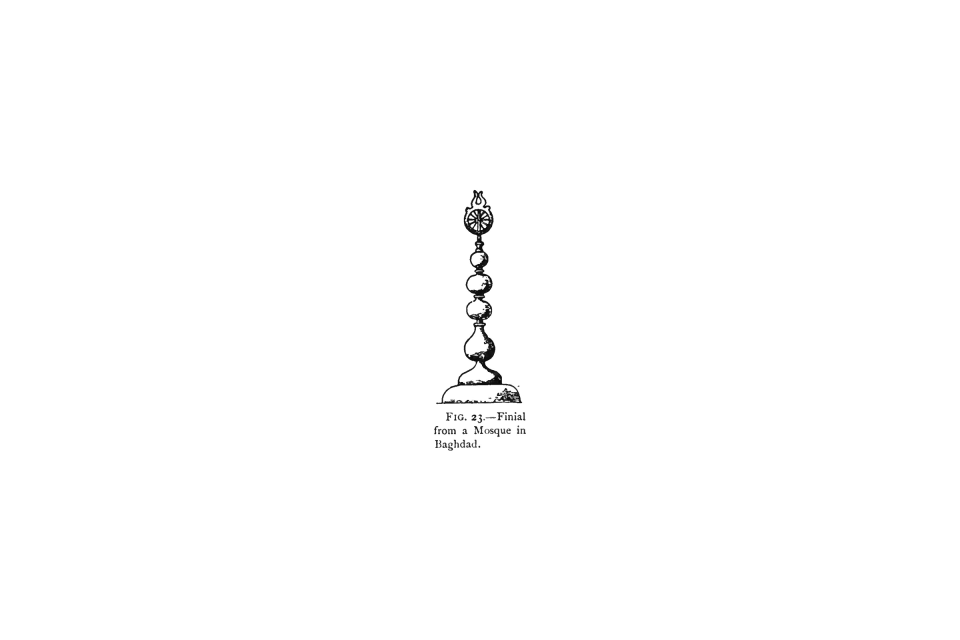

Saracenic architecture in Persia shows many indications of Buddhist influence. I have before alluded to the fact that the Persian name for the pinnacle or finial of domes is taken from the Indian word kalasha, the water-pot. The combination of forms used in the metal finials of Persian domes also indicates a survival of Buddhist symbolism. The three balls in fig. 23 recall the three umbrellas of the Buddhist tee; the other shape is the Indian water-pot. Still more significant is the fact that several of the finials from Persian and Arabian mosques illustrated by Dr. Langenegger11 are surmounted not by the ensign of Islâm, but by the chakra, the wheel of the Law!

It was therefore perfectly easy for any Indian craftsman, whether Buddhist, Hindu, or Muhammadan, to recognise this Saracenic art as his own, in spite of its foreign disguise. The Indian builders did in fact from the very first treat it frankly as belonging to their own art tradition. Their only endeavour was to divest it of its foreign accretions; and the fact that they consistently did this, unchecked by their Muhammadan employers, so that Muhammadan architecture in India never became more “Saracenic” than the Indian builders wished it to be, is clearly stated in masonic language on all Indian Muhammadan buildings.

A most significant fact, unnoticed by Fergusson, and I believe by all other writers, is that with the rarest exceptions the domes of every Muhammadan building in India, beginning with the mosques at old Delhi and Ajmîr, are crowned not with the symbols of Islâm, as recognised by true believers in Persia, Arabia, Egypt, or Turkey, but by the Indian kalasha, the amalaka, or the lotus-flower—the traditional symbols which surmounted the vimânas and mandapas of Hindu temples.

Nothing could more clearly explain the mental attitude of Hinduism towards the followers of Islâm. “We build these mosques and tombs for you,” these Indian masons say, “we set our sacred symbols upon them; for the God whom you know as Allah is Brahma and Vishnu and Siva. You may kill us and destroy our temples, but our bhakti is not destroyed. Vishnu and Siva are here, even in these stones. Though you only bend your knees to Allah, Brahmâ is immanent in every prayer.”

Any student with insight into the philosophic attitude of Hinduism who learns to read the symbolic language of these Indian Muhammadan monuments might well believe that most, if not all, of the craftsmen who built them were Hindus at heart, eventhough professed followers of the Prophet. In all the lndian Muhammadan styles of Fergusson’s academic classification—at Delhi, Ajmîr and Agra, Gaur, Mâlwâ, Gujerat, Jaunpur, and Bijâpûr—whether the local rulers were Arab, Pathân, Turk, Persian, Mongol, or Indian, the form and construction of the domes of mosques and tombs and palaces, as well as the Hindu symbols which crown them; the mihrâbs made to simulate Hindu shrines; the arches Hinduised often in construction, in form nearly always; the symbolism which underlies the decorative and structural design, all these tell us plainly that to the Indian builders the sect of the Prophet of Mecca was only one of the many which made up the synthesis of Hinduism: they could be good Muhammadans but yet remain Hindus.

Let us now proceed to examine further the symbolism and structure of these Muhammadan domes. In spite of a very general uniformity of structure, there is considerable variety in the external form of Indo-Muhammadan domes in the thirteenth, fourteenth, and fifteenth centuries; but usually they are of three distinct types—first, a conical form following the internal section; secondly, the so-called “Pathân” dome with its flattened top and strongly pronounced haunches; and lastly, the hemispherical or semi-elliptical. The Hindu horizontal system of dome-building could never produce a hemispherical shape internally, and if a Hindu dome of solid masonry were made of the same thickness throughout, the exterior would present the rather ugly conical shape which is seen in many of the early makeshift domes of Muhammadan mosques and tombs (Pl. XIV). The Gujerat builders often tried to meet this æsthetic difficulty by bringing the exterior approximately to a semi-circular section, as in the domes of the side-aisles of the Jâmi’ Masjid at Champanîr (Pl. XLIX). This, of course, meant an increase in the thickness of the domes in the wrong place, and a great waste of material. The “Pathân” dome was a much better expedient: it was the most scientific, and on that account the most beautiful, curve an Indian craftsman could adopt when he was obliged to puritanise the exterior of the traditional Hindu dome by leaving out the sculptured symbolism. The section of the dome of a typical Hindu porch (fig. 24) will show this. If the external excrescences of the sculptured masonry are removed, the dome will be naturally transformed into a “Pathân” dome (Pl. XCI). This was frequently done after the Muhammadan conquest, as I have shown already, not only in Muhammadan domes, but in the domes of the porches of Hindu temples.

There was, however, another practical alternative. When a hemispherical dome was wanted, the builder could use stone ribs for the structural framework and fill up the interstices with horizontal courses of stone or with rubble masonry. By this means the dome could be made of convenient thickness throughout. There was no need to look to Western models for this ribbed method of construction, for not only were all the wooden and bambu domes of the Buddhist builders constructed on this principle, but the stone-ribbed sikharas of Hindu vimânas and portions of the roof of the mandapas also. The ribbed dome of the Jâmi’ Masjid at Champanîr (Plate L) is, therefore, not a borrowing of a Western fashion, but an intelligent Indian craftsman’s expedient for constructing a hemispherical dome scientifically according to the Indian craft tradition. The central dome with its sixteen ribs—two for each petal of the Mahâ-padma, is both in structure and symbolism as much Hindu as are those of the side-aisles which are built entirely in horizontal courses.

Now, according to the Buddhist and Hindu tradition the tee or finial of a dome should rest either upon the amalaka or upon the Mahâ-padma—an eight-petalled lotus with the petals turned downwards both of which were sun-emblems. The springing of the dome, or the outer rim of the bell, was also ornamented with a row of lotus petals, which suggested that the dome itself grew out of the heart of a lotus flower. Bearing this in mind, we can follow the Indian craftsman’s intention in the external decorative treatment of Muhammadan domes. There are three successive stages. The earliest Muhammadan domes had no external ornamentation except the Hindu finial—the bell of the dome was simply plastered over roughly on the outside. Then the domes are carefully finished externally either with glazed tile-work or with a facing of brick or stone, and the octagonal base is ornamented in the same manner as the parapet of a Hindu fortress wall, sometimes with a suggestion of the lotus leaf or petal, sometimes with the Persian iris worked into it (Pl. XL), but with an obvious intention of reverting to the old Indian masonic tradition, for it was not usual in Arabian or Persian buildings to ornament the external springing of the domes in this manner. Finally, in the Tâj Mahall, and still more distinctly in the domes of the Bijâpûr and Golconda buildings, the Buddhist lotus dome—the “bulbous” one—reappears in a modified form with all its traditional members, according to the Hindu Silpa-sâstras, the base of every “bulbous” dome being enclosed with strongly marked lotus petals (Pl. LXXXV).

This brings us to the further consideration of the interior treatment of Muhammadan domes and of that great triumph of idealistic engineering of the Bijâpûr builders in the tomb of Mahmûd (1638-60), the last but one of the Bijâpûr dynasty, justly described by Fergusson as “a wonder of constructive skill.” For the first few centuries of Muhammadan rule in India the interior decoration and construction of the roofs of mosques and tombs presented no essential difference to those of Hindu temples, except in the absence of anthropomorphic symbolism. The lotus flower and the chakra, either separately or in combination, formed the usual basis of the decorative scheme in both cases. Neither was there any difference in constructive principles until the size and weight of the domes in Muhammadan buildings were so greatly increased that provision had to be made for counteracting the outward thrust of these great masses of masonry or brickwork.

The early Indian domed canopy must, as I have explained above, have been constructed on the same principles as modern Persian domes, that is, it had an outer and an inner dome, the outer, or false, dome being merely a shell of mud, plaster, or concrete, of so light a character that nothing more was needed for stability than the inner ties of wood or rope attached to the central post which kept the pinnacle in its place. But in this case, as in so many other, the early practice established a traditional constructive principle which was followed when more permanent materials were used—that is to say, the double roof became a constructive feature in the porches of Hindu temples in Northern India, even when they were built of solid masonry, and Indian builders were accustomed to the idea of counteracting the lateral thrust of a dome from the inside of it. This was the antithesis of the Western idea, which was to build external buttresses and to pile great masses of masonry on the haunches of the dome—as Fergusson says, a very clumsy expedient.

The domes of the porches of Hindu temples in Northern India were usually supported on pillars arranged as in fig. II, the difficulty of supporting the octagonal base of the dome being surmounted, when the latter was of large dimensions, by brackets or stone struts between the pillars. The same principle was followed in all of the early Muhammadan mosques, but the sanctuary of a tomb was often enclosed by walls, like the shrine of a Hindu vimâna, and in this case pendentives would be more convenient to use at the angles whenever the stone beams at the base of the dome required this support.

Pendentives would also become a useful constructive expedient, if not an organic necessity, when, in order to gain more floor-space, the pillars supporting the octagonal base of the dome were dispensed with and the four corner pillars or piers were joined by arches. In Malik Mughis’ mosque at Mandû (Pl. XIX), a very interesting example of the transition from the trabeate to the arched system of building, the capitals of the four corner pillars engaged between the arches are used as brackets to support the base of the dome in the ordinary Hindu method; but here the dimensions are small and the extra eight pillars would not have been necessary if arches had not been used. The usual type of pendentive in early Muhammadan buildings was a solid corner bracket corbelled out of the walls, and often treated decoratively with cusped Hindu arches, as in fig. 25. But when Indian builders got accustomed to using arches of considerable size12 structurally instead of pillars and brackets to support the octagonal base of the dome, the arched pendentive naturally came into use also. A rather crude early-fifteenth-century application of it can be seen in the Jâmi’ Masjid at Mandû (Pl. XVIII). It is important to notice that in this building rubble and brickwork were largely used instead of pure lithic construction, for it was the technique of brick construction which led up to the great engineering achievements of the Bijâpûr builders in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.

The germ of the idea of the Bijâpûr dome can be seen in two Muhammadan buildings in Gujerat, which Fergusson has left unnoticed in his history, though structurally they are very important—the tombs of Daryâ Khan and the mosque of Alif Khan, belonging to the middle of the fifteenth century. Both are of brick, both have hemispherical domes, like the Jâmi’ Masjid and Mahmûd’s tomb at Bijâpûr, and both have some apparent Persian affinities, although on closer examination it is evident that they are the work of Indian builders working out for themselves engineering problems which the Muhammadans in Persia never attempted to solve. Even Fergusson does not deny the originality of Gujerat architecture. “No other form,” he says, “is so essentially Indian, and no one tells its tale with the same unmistakable distinctness.”13 The larger Perso-Saracenic domes are thin shells of so light a character that an internal wooden framework often sufficed for their support. Their builders, in an engineering sense, never progressed farther than the domes of the Indian Buddhist builders. Perso-Saracenic buildings on the whole seem hardly to belong to the domain of architecture—they are rather magnificent chefs-d’ œvre of painted china or majolica supported by a wooden framework and strengthened with a core of brick to make them habitable. The Mongolian invasion of Western Asia seems to have swept away in its terrible holocaust the great Sassanian building traditions, so that when the later Persian and Chinese fashions were brought into India by the Muhammadan invaders, it was left to the Indian masons, who since the palmy days of Buddhism had progressed much farther than the Persians in masonic craftsmanship, to teach their masters what could be done in brick and stone.

The tomb of Daryâ Khan is near Ahmadâbâd, a mile north of the Delhi gate. Dr. Burgess gives the date ascribed to it, 1453, and the dimensions. The plan is the usual one of Muhammadan tombs in India. The sanctuary containing the tomb is a square of about 50 feet, covered by a single large dome raised on a circular drum, and surrounded by corridors 19 feet wide, which are enclosed by walls with five arched openings on each side and divided into five corresponding square compartments roofed by small domes. The central dome is built in the following manner: At a height of 17 feet from the floor a small bracket pendentive is corbelled out of each of the four corners of the central hall, the base of it being shaped in successive courses of brickwork like the arched head of a mihrâb. These corner brackets, or pendentives, above the arched base are brought to a plane surface of about 7 feet wide reducing the upper part of the hall to an irregular octagon; and at a height of 29 feet they support a plain string-course or plinth, carried right round the building, which serves as a base for four larger arches 17 feet wide, built in front of the corner brackets. These larger arches reduce the walls to a regular octagon, according to the usual Hindu practice. Light is admitted into the building by windows placed in the centres of the four main walls just above the string-course. The octagon is reduced to a sixteen-sided polygon by filling up the angles with eight smaller brackets; and at a height of 45 feet from the floor another string-course or cornice serves as the starting-line of the circular drum of the dome, which is 17 feet in height. The brickwork of the drum and dome is laid in successive horizontal rings about 4 feet in height, as if to simulate the Hindu lithic construction. The total height inside is 86 feet. The usual Hindu finial crowns the top of the dome, and the springing of it is marked outside by the lotus-leaf parapet, which is not found in any Arabian or Persian domes. In fact, the whole building is structurally as characteristically Indian as are all the other Muhammadan tombs and mosques in Gujerat.

Alif Khan’s Masjid at Dholkâ, about twenty-three miles to the southwest of Ahmadâbâd, has a lîwân, or sanctuary, divided into three compartments, each about 43 feet square, covered by domes approximately hemispherical. It was built about the same time as Daryâ Khan’s tomb, but the arrangement for the support of the domes is more elegant and marks a distinct advance in architectural skill, though the domes are smaller, being about 41 feet in diameter, or 9 feet less than that of the other building. The beautiful stucco work of the entrance doorways is shown in Pl. XXVII. The plan and section drawn by Mr. Cousens (figs. 28 and 29) will explain the construction of the domes. At a height of about 23 feet from the floor, says Dr. Burgess, a plain string-course runs along the walls and is surmounted by eight arches—four of them with groins across the corners, so as to reduce the square to an octagon—the four on the sides enclosing perforated windows through the outer walls and plain openings through the inner ones. These arches, with groined segments between their haunches, reduce the space, at a height of 38 feet from the floor, to a sixteen-sided polygon, with a plain stepped moulding laid over the cusps to form the base of the dome, which rises to a height of 63 feet from the floor inside.

Now let us compare these two much greater and more famous buildings at Bijâpûr, the Jâmi’ Masjid, begun in the latter half of the sixteenth century, and Mahmûd’s tomb, nearly a century later. Fergusson’s description of the great dome of the latter, which will serve to explain both, is as follows:

“As will be seen from the plan (fig. 30), it is internally a square apartment 135 ft. 5 in. each way; its area consequently is 18,337 sq. ft., while that of the Pantheon at Rome is, within the walls, only 15,833 sq. ft.; and even taking into account all the recesses in the walls of both buildings, this is still the larger of the two.

“At a height of 57 ft. from the floor line the hall begins to contract, by a series of pendentives as ingenious as they are beautiful, to a circular opening 97 ft. in diameter. On the platform of these pendentives at a height of 109 ft. 6 in., the dome is erected 124 ft. 5 in. in diameter, thus leaving a gallery more than 12 ft. wide all round the interior. Internally, the dome is 178 ft. above the floor, and externally 198 ft. from the outside platform; its thickness at the springing is about 10 ft., and at the crown 9 ft.

“The most ingenious and novel part of this dome is the mode in which the lateral or outward thrust is counteracted. This was accomplished by forming the pendentives so that they not only cut off the angles, but that, as shown in the plan, their arches intersect each other, and form a very considerable mass of masonry perfectly stable in itself; and by its weight acting inwards, counteracting any thrust that can possibly be brought to bear upon it by the pressure of the dome. If the whole edifice thus balanced has any tendency to move, it is to fall inwards, which from its circular form is impossible; while the action of the weight of the pendentives being in the opposite direction to that of the dome, it acts like a tie, and keeps the whole in equilibrium, without interfering at all with the outline of the dome.

“In the Pantheon and most European domes a great mass of masonry is thrown on the haunches, which entirely hides the external form, and is a singularly clumsy expedient in every respect, compared with the elegant mode of hanging the weight inside.”

If Fergusson had not been obsessed with the idea that the greatness of Indo-Muhammadan architecture was due to Saracenic inspiration, he would have seen that though much grander on account of their colossal dimensions and finer in architectural treatment, the Bijâpûr domes of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries established no new principle in engineering, but with a single modification followed exactly that on which the two Gujerat buildings had been constructed in the fifteenth century. In both of the latter the weight of the pendentives at the base of the dome acts as an internal tie, the mechanical principles being similar to that which was used by the early Buddhist builders, though the lateral thrust of these smaller domes would be insignificant compared with that of Mahmûd’s colossal tomb. The only difference, from an engineering point of view, was that on account of the lateral thrust being so much greater, the inner circular string-course, or cornice, at the springing of the dome had to be much heavier and thrown more inwards.

The way the Bijâpûr builders effected this was as ingenious as it was beautiful; but the idea was Indian, not Saracenic. Indian builders in the sixteenth century had become familiar with the Persian pendentive, formed by intersecting brick arches. The light Persian pendentive, however, would not have served their purpose, so, like good craftsmen, they invented a new way of using it—a combination of the Hindu and Saracenic methods with Hindu idealism behind them.

In the tomb of Daryâ Khan, though arches are used in the pendentives, the pendentives themselves are arranged on the Hindu bracket system—i.e. the square base of the dome is converted into a circle gradually by tier upon tier of bracket pendentives placed in horizontal and vertical planes only. In the Dholkâ mosque the principle is the same, but the upper tier of brackets below the springing of the dome combines with the arches of the lower ones in forming a decorative scheme like the petals of a half-opened lotus flower—a device characteristically Hindu. The Jâmi’ Masjid and Mahmûd’s tomb at Bijâpûr show a variation of the same treatment, in which the resemblance to lotus petals is made more complete by the intersection of the arches. This produced not only the mechanical result which was aimed at—that of a sufficient centra-weight to the lateral thrust of the dome—but it achieved also the artistic ideal which the Indian builders had in their mind, to support the dome on the symbolic lotus flower, the eight petalled Mahâ-padma formed by the groining of the pendentives, which repeats internally the Mahâ-padma on which the finial of the dome is placed.

Thus we find both the artistic idealism and the practical craftsmanship of the Hindu and Buddhist building traditions inspiring the Muhammadan builders in all their greatest works. Unless the archæologist relies upon examples in which Indian inspiration is conspicuous, he will search in vain in Central Asia, Persia, Arabia, Egypt, or in Europe for Saracenic buildings which explain either thesymbolism or theconstructive principles of the great Muhammadan buildings in India. The true history of Indian architecture, Buddhist, Hindu, and Muhammadan, is written in the monuments which exist only in India itself.

- 1. Professor Rhys Davids has shown that according to Buddhist teaching the attainment of Nirvana is a purely spiritual achievement, and does not necessarily imply the dissolution of the physical body.

- 2. Modern Review, Calcutta, July, August, 1910.

- 3. Dr. Felix Langenegger in “Die Baukunst des Irâq” (Gerhard Kühtmann: Dresden, 1911) illustrates one of these (fig. 45).

- 4. “Architecture,” p. 145.

- 5. The cusped arches of the Chota Sonâ Masjid are not the earliest of their kind in Muhammadan buildings in India, though they are most interesting as revealing, clearly the mental process by which the Indian craftsmen worked them out. There are similar arches in the tomb of Altamsh at Old Delhi (c. 1235), and it is quite possible that the Indian masons brought by Mahmûd to Ghaznî had arrived at the same form of structural arches by a similar mental process. The main point is that the derivation of this form of cusped arch is Indian, not Saracenic.

- 6. “Indian Architecture,” vol. ii. p. 57.

- 7. See pp. 25-6.

- 8. See Saladin, “Manuel d’Art Musulman,” fig. 276, p. 361.

- 9. Langenegger, “Die Baukunst des Irâq,” fig. 129, p. 101.

- 10. It is very probable that this ornamental treatment had its origin in the practice of using earthenware pots to lessen the weight of concrete domes and vaults; and it is quite possible that the practice of using pottery in this way suggested the stalactite pendentive of the Arabs, as it was certainly the earlier of the two methods.

- 11. “Die Baukunst des Irâq,” p. 121.

- 12. I assume that before the Muhammadans came, the Buddhists and Hindus had only used arches of small dimensions structurally, in brick-building districts like the Magadha country.

- 13. “Indian Architecture,” vol. ii. p. 229.