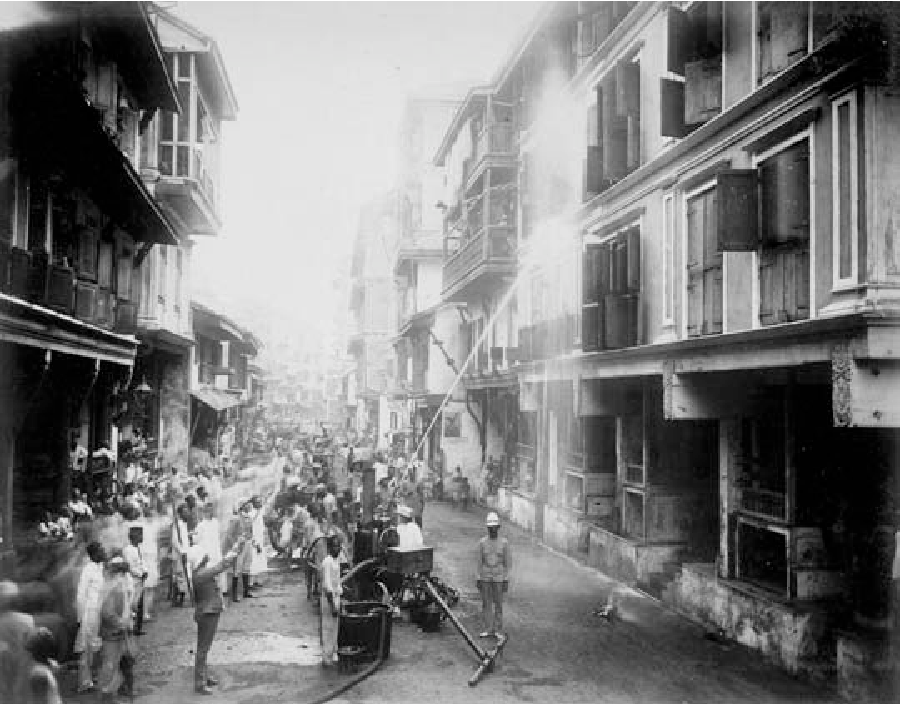

In September 1896, a virulent plague epidemic broke out in the colonial port city of Bombay. Central to existing interpretations of the epidemic has been the pervasive assumption that colonial policies aimed at suppressing the disease were principally informed by ‘contagionist’ etiological doctrine. However, this article argues that long-standing ‘localist’ etiological theories continued to exercise a critical influence over colonial policies. It thereby highlights the explicit ‘class’ bias that informed the colonial state's anti-plague offensive, which was largely directed at the urban poor.