Since its inauguration in 1993, the Jawahar Kala Kendra has been one of the most significant buildings for architects around the country. In many ways, it embodies some of the most important ideas of Charles Correa through its open to sky spaces, its public orientation and its humane scale. The building is important to the city of Jaipur as a foremost effort that folds history and modern efforts together to create a public space par excellence. An exhibition on architecture has been waiting to take place at the JKK.

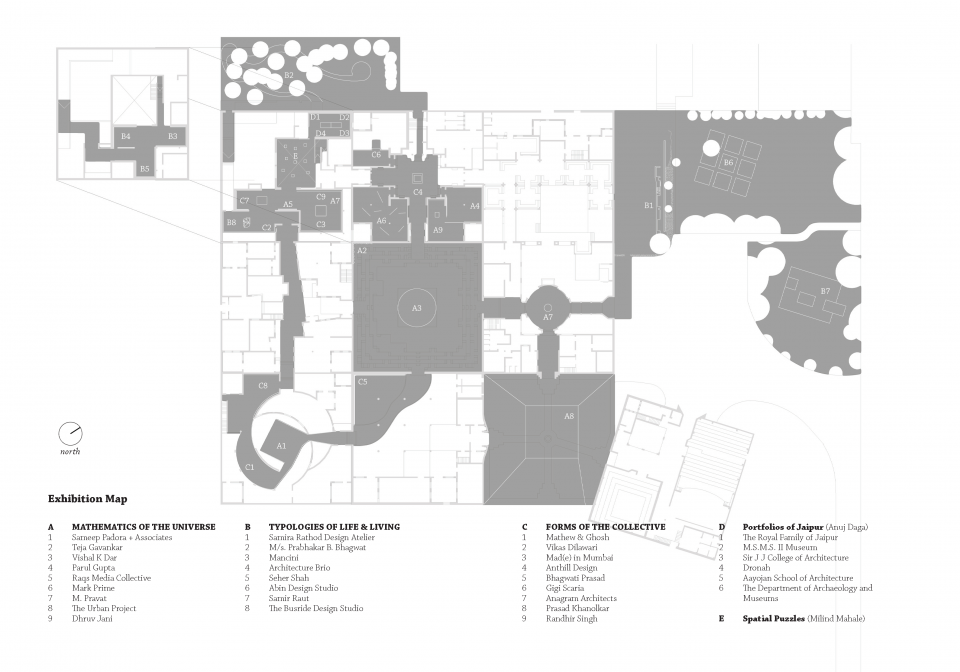

I am delighted to present this exhibition titled ‘When is Space?’ curated and designed by Rupali Gupte and Prasad Shetty. This project has a conceptual ambition of tying together the visions of Sawai Jaisingh, the ideas of Charles Correa and the practices of contemporary architects and artists. The exhibition is being put together as a set of provocations from the works of Charles Correa and the city of Jaipur with responses from 27 participants including architects, artists, designers, photographers and social scientists. The Sawai Mansingh II Museum of Jaipur has also graciously agreed to lend some of the archival material for the exhibition. Along with these, two schools of architecture - Aayojan School in Jaipur and JJ College in Mumbai are also involved.

It is for the first time that an architecture exhibition of this format is being shown at JKK where architects and artists are involved in actively engaging with its spaces. It is an exhibition on the explorations of space. We hope this sets the tone for many more artistic journeys, where various disciplines come together to prise open new terrains of thinking about and making architecture.

Pooja Sood

Director General, Jawahar Kala Kendra

When is Space?

‘When is Space?’ discusses contemporary architecture and space-making practices in India. The historic city of Jaipur established by the astronomer-king Sawai Jai

Singh and the Jawahar Kala Kendra, one of the most significant buildings of Charles Correa, provide an apt context for this exhibition. A large part of contemporary space-making practices appears to be structured around three imperatives: first, computational and mathematical logics aided through a variety of devices including digital media; second, environmental and cultural responsiveness that manifests as new building typologies; and third, concerns regarding city and public that produce urbanistic practices of research and advocacy. These imperatives were also central to the pursuits of Jai Singh and Charles Correa. The obsessions with the astronomical mathematics; the desire to reinvent building types, and the aspiration to create a just and sustainable city are dominant in the ambitions of both individuals. The exhibition has a conceptual ambition of tying together the visions of Sawai Jai Singh, the ideas of Charles Correa and the concerns of contemporary space-making practices. Towards this, three provocations are articulated:

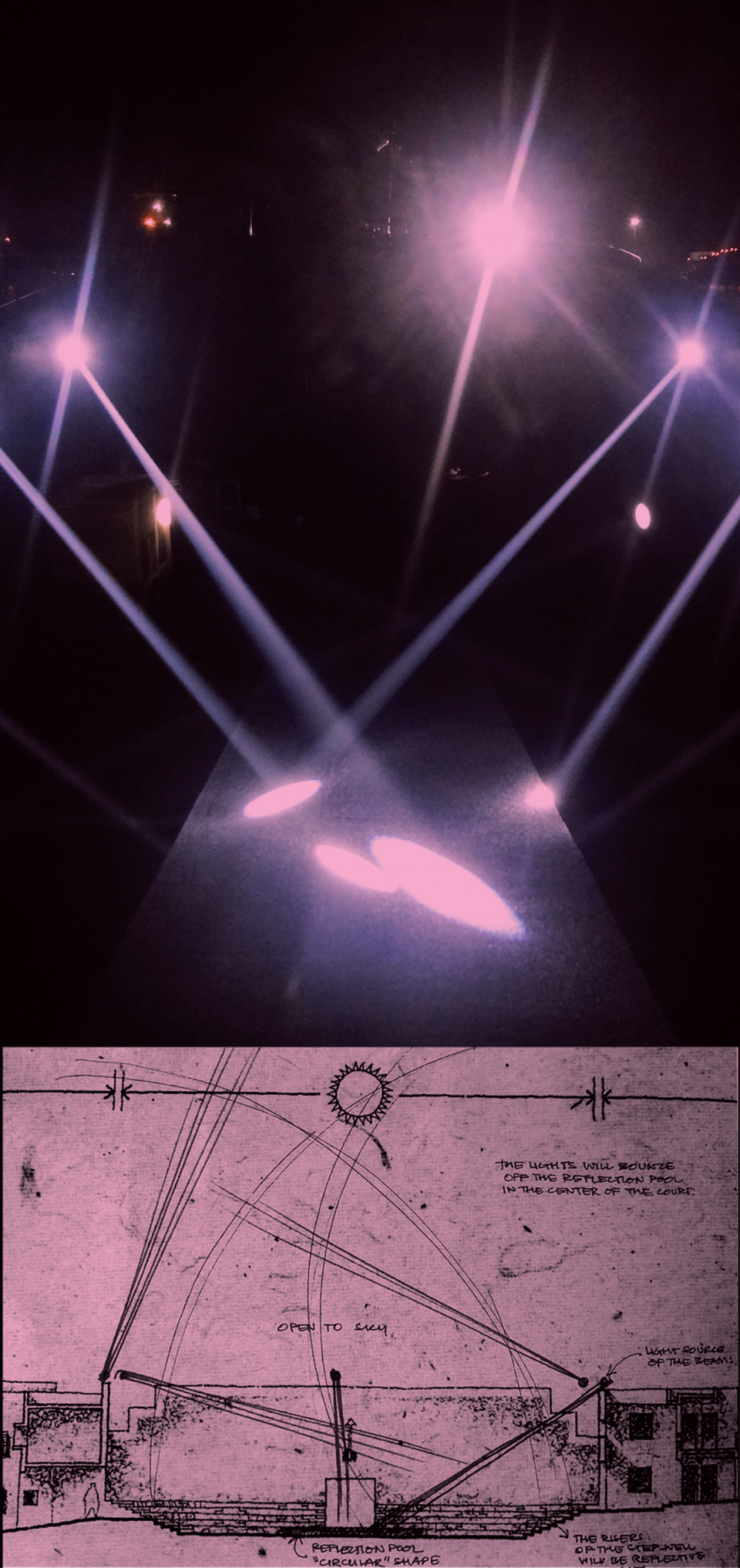

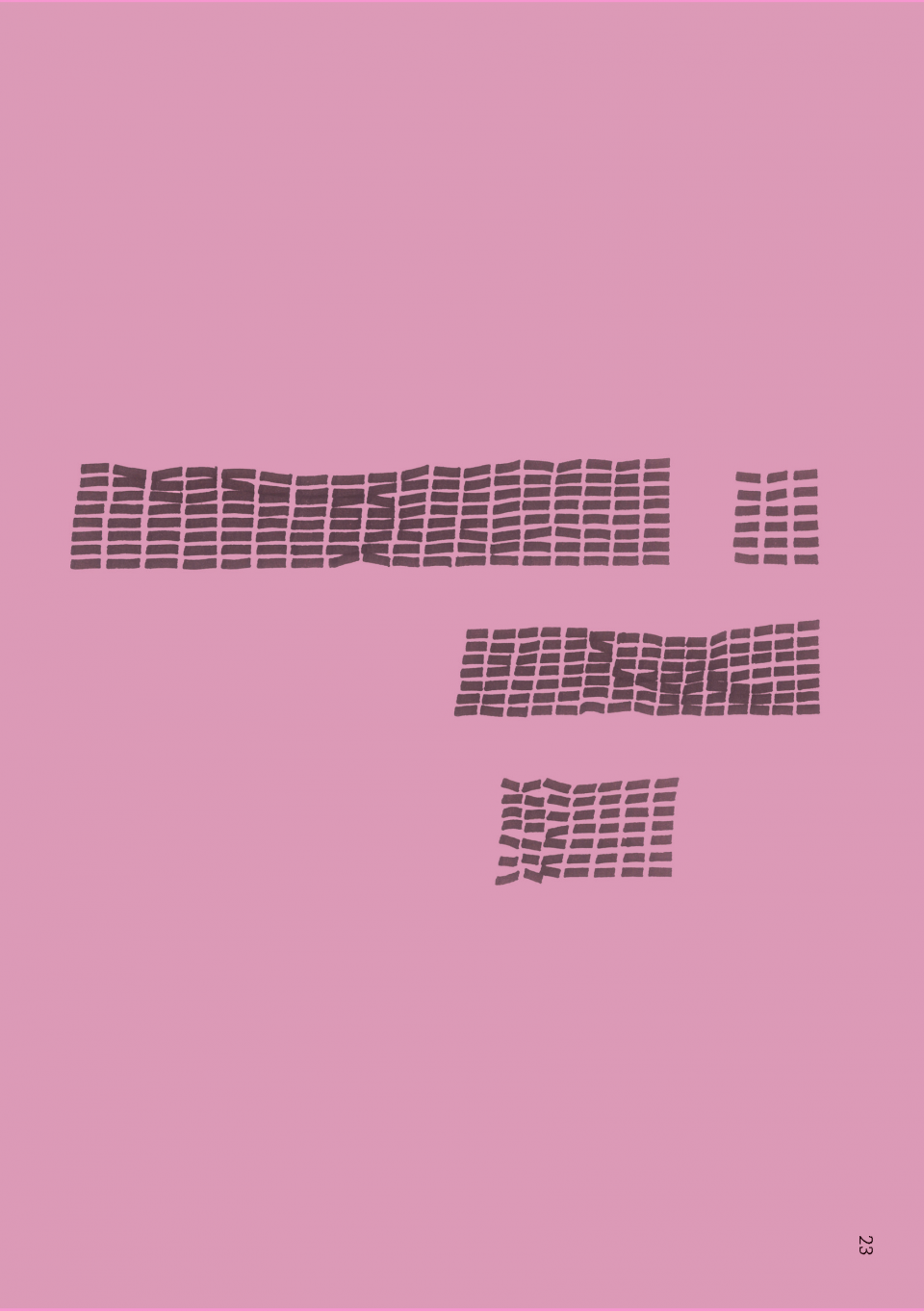

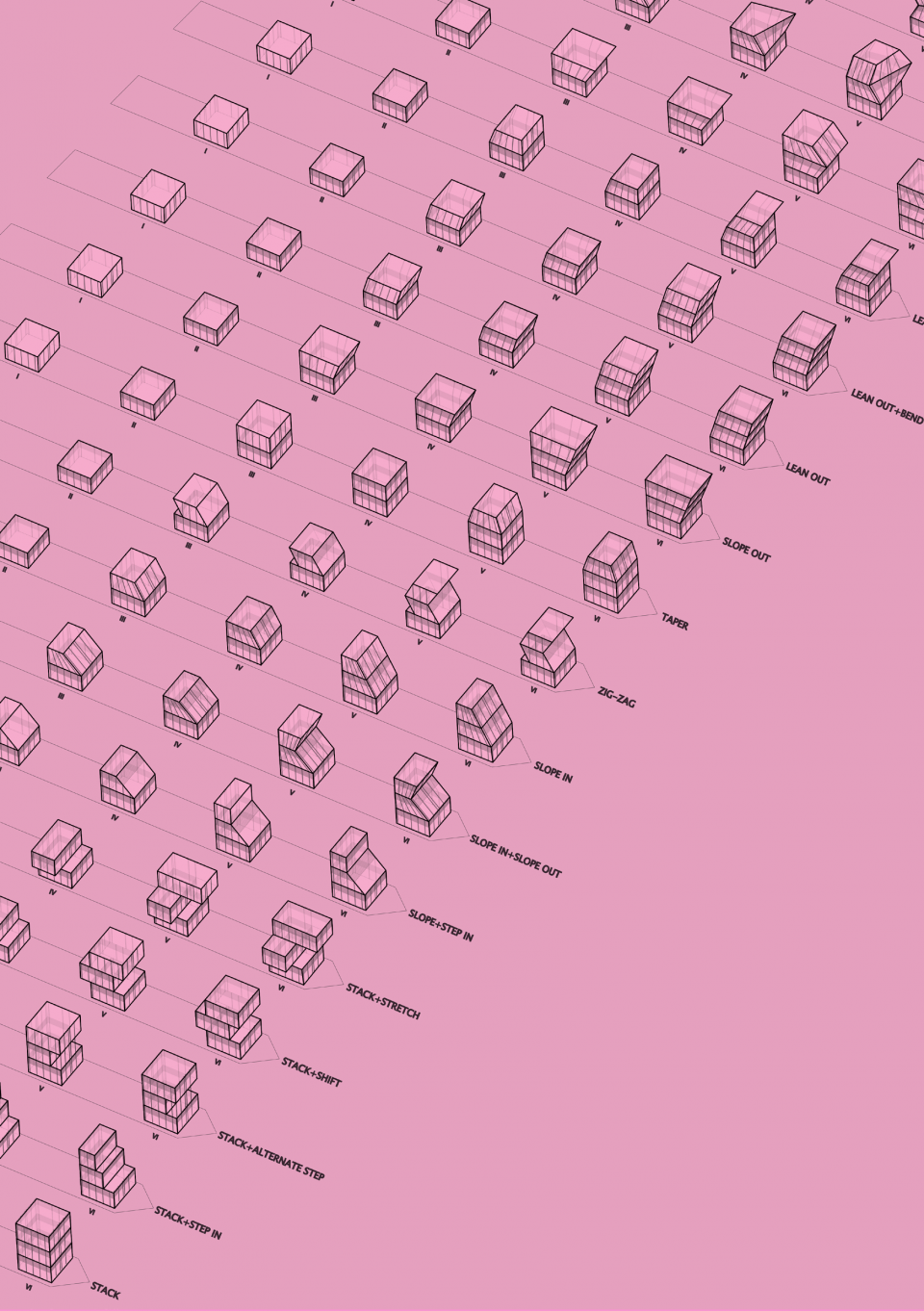

Mathematics of the Universe: The notion of boundary is crucial to thinking about space. However, this very idea of boundary limits our imagination of the universe. It is probably in the fractals, multiples and geometry as much as the errors, glitches and slippages that the experience and form of the universe can be conceptualised. What happens when this mathematical logic is mobilised to (re)invent form and space – does it provide a hint to the logic of the universe?

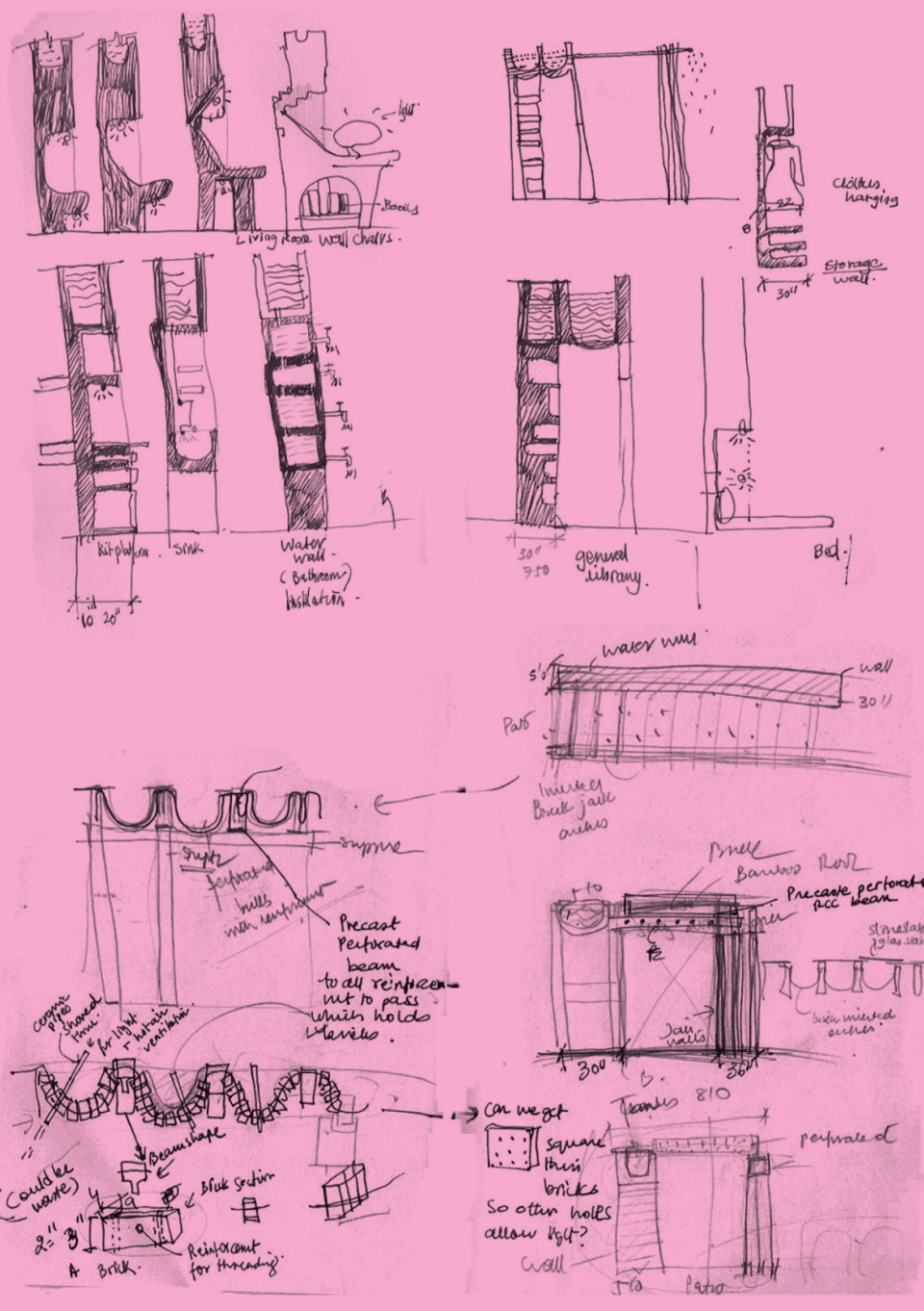

Typologies of Life and Living: Different forms of life-forces – work, leisure, craft, religion, celebration, governance, etc. constantly co-produce each other. Over time patterns develop in them which can be identified as typologies. While typologies consolidate culture, they may stagnate life in set moulds. What happens when built- form typologies are interrogated and transformed – what new forms of living get produced?

Forms of the Collective: Imaginations of collective life manifest themselves as cities. Here, specific urban forms emerge, that complement as well as reproduce the collective. As the collective is a complex entity that is composed of a variety of practices and desires – the urban forms they inhabit are usually contested. Can there be an urban form that can afford the multiplicity of the collective – what are the enabling infrastructures and new logics for exploration of life, hope and enterprise?

‘When is Space?’ includes the works of architects, artists, designers, urbanists, architecture colleges and museums, who were invited to respond to the above provocations through spatial interventions within JKK. ‘Space’ here encompasses multi-scalar notions to include the space of the universe, social space, landscapes and microenvironments. How do we begin to understand space? What does it take for space to happen? This exhibition puts together a series of explorations in making space – by mobilizing claims, constructing narratives, recalibrating boundaries, responding to contexts of economy and ecology and interrogating conventional processes. How can different disciplines productively engage in the pursuit of

space making? What are the new vectors for practice and discourse of space? With an affective landscape of spatial interrogations, Jawahar Kala Kendra is imagined as a laboratory for experiments that shall not only locate the present concerns of contemporary architecture, but also trace its future trajectories.

Rupali Gupte & Prasad Shetty

Curators

“To invent a new future and to rediscover the past is one gesture.”

Maharaja Jaisingh (1687 - 1743)

Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru (1889 - 1964)

reinstated by Charles Correa (1930 - 2015)This compilation invigorates the above epigram that greets the viewer at the Jawahar Kala Kendra before an(y) exhibition begins. In a manner of underlining this subtle provocation, the work summaries of participants here are juxtaposed with a historical reading of Jaipur as well as writings of Correa. Such an intervention produces new readings of the installations and opens up another spatial dimension of JKK.