This image is embedded in ...

- Ganju, MN Ashish, Sheba Chachhi, Jogindar Panghal, and Dr K. L. Nadir. Migration, Living and Earning, Shelter Meanings, Quality of Life. GREHA. Delhi, India: Greha, 1981.

Concerning detail, exhibitions and photo-essays

Nomothetic cases, project reports and research articles

Observations on the state of affairs in South Asia

Conversations, Presentations and Recordings

Policies and curricular matters in Architecture-related subjects

Concerning professional space, practice, and contests

GREHA (गृह) Document Archive

Nomothetic cases - frequently cited buildings and projects

Master Plan Implementation Support Group, '00-06

Publications by Architexturez and others

Right to Information cases from MPISG and Enaction collections

Essays, reports, research. texts and 'histories'

Delhi is a city of immigrants.

Most of them have come here after 1946. They came for specific historic reasons, and most of them are now settled. They had some resources, and the policy-makers had the will and resources to settle them. A trickle of such people, with their own resources, still continues, but this does not pose a problem for the city.

There is another stream of migrants who form a perennial source of supply to the city.

Within this stream three tributaries contribute to the inflow:

These people generally constitute the very poor in rural India. They are landless labour, largely drawn from Scheduled Casts and Tribes, possessing only the traditional skills associated with their castes.

This image is embedded in ...

Those who move out of their rural habitat prefer to move to large cities within their cultural region.

Delhi is a city-state which is at the centre of the region comprising UP, Rajesthan, Haryana, Punjab, HP and J&K. The bulk of migrants, not surprisingly, come from the adjacent states of UP, and Rajesthan where the rate of urbanisation and industrialisation is low. Specifically the depressed rural areas, such as Eastern UP, contribute large numbers.

Yet there are migrants from far-off places, who are a class by themselves, constrained by specific and peculiar circumstances which push them out of their regions.

This image is embedded in ...

Having come with inappropriate attitudes and values to an alien world, and handicapped by devalued skills, the migrant has to find the means to understand the environment in which he has to operate. Illiteracy hampers the process of surveying the environment.

The migrant's immediate concern is the earn a living and to find shelter. Kinship networks help in locating potential job opportunities and sources of credit. These information networks of the poor provide a highly efficient and reliable system for connecting with the myriad sub-systems of urban life.

The migrant has to learn the ways of life within the city. He needs fresh schooling for socialising him into urban ways -- to understand the formal structures of the city as well as its unwritten codes of conduct. The migrant learns through the informal channels about the nooks, crannies and niches in the city system, where, in spite of his handicaps, he can fit in and make a place for himself.

The networks of the poor function like a transitional field where the migrant is equipped to meet the challenge of urbanisation In the process he changes himself and leans to adapt to the urban way of life.

This image is embedded in ...

Driven by the need to retain some control over their destiny, and to operate in a world with which they are familiar, the recent migrants like to be in a little village within the city. They seek to insulate themselves in a world of their own which might be immune from assault by the urban forces. To assure themselves that their familiar identities are not distorted in a situation where they see themselves as besieged, they seek psychological support from their kinfolk. Thus the affinities of caste and kin are asserted with a vengeanceby the pressures of urban life drive them into new affinities and styles of life. The economic system of the city compels them to individualise their effort, thus imperceptibly altering the traditional cooperative culture of their rural background.

Simultaneously the traditional caste loyalties metamorphose into new political loyalties. Migrant communities learn the ways of exchanging their political support with welfare measures to ameliorate their condition.

This image is embedded in ...

Agricultural labour households who are unable to eke out a bare living are motivated to migrate in order to survive, most of them permanently and some of them seasonally.

A variety of reasons, both economic and social, cause this condition.

The capacity of the poor to fight back for social and economic rights within the given framework leads to an intensification of their oppression.

This forces regular movement out of the villages. Such migration assumes epidemic proportions during periods of draught and famine.

In addition, young, single migrants from villages, who are slightly better placed to migrate in terms of their skills and resources, are pulled to the urban centres. They are attracted by the urban way-of-life through exposure to hte mass media, their kinship communication networks, and causal contact with the city.

This image is embedded in ...

These poor migrants come to the city, without resources or skills relevant to urban life. They do not have even the social learning necessary to understand the urban world around them. With their traditional skills devalued in the urban circumstance, most of them find that they can only be unskilled labourers. alienated, they are forced into an unequal struggle against a hostile environment.

Driven by the sheer instinct for survival they manage to find a place only in the lowest rungs of the social and economic order.

They have no capital to help them survive the transition from rural to urban life. During this period of transition the social network of a competitive rural culture is in a way the only resource they can rely on.

This image is embedded in ...

The place of these very poor in the economy of the city is peculiar.

Driven by the sheer instinct for survival they manage to find a place only in the lowest rungs of the social and economic order.

They are a ready source of cheap labour who can be employed whenever needed, without burdening the employers with the liabilities of regular wages and social security payments.

In that sense they are needed, and become essential to the functioning of the peculiar economy of the mixed system of enterprise.

If viewed from a normative angle, fewer people employed on a regular basis could have possibly performed the functions as well. Though the question will remain whether the present economic structure would be able to bear the cost.

A major segment of these poor people are petty traders and producers. They work with the most primitive tools and hardly any capital. The production and retailing is split to the ultimate extent when the earnings at the bottom are at substance level.

This image is embedded in ...

This image is embedded in ...

They have no resources to augment their basic human capacity for work. The will to survive has to operate at a level which is really an interface between the animal and human world.

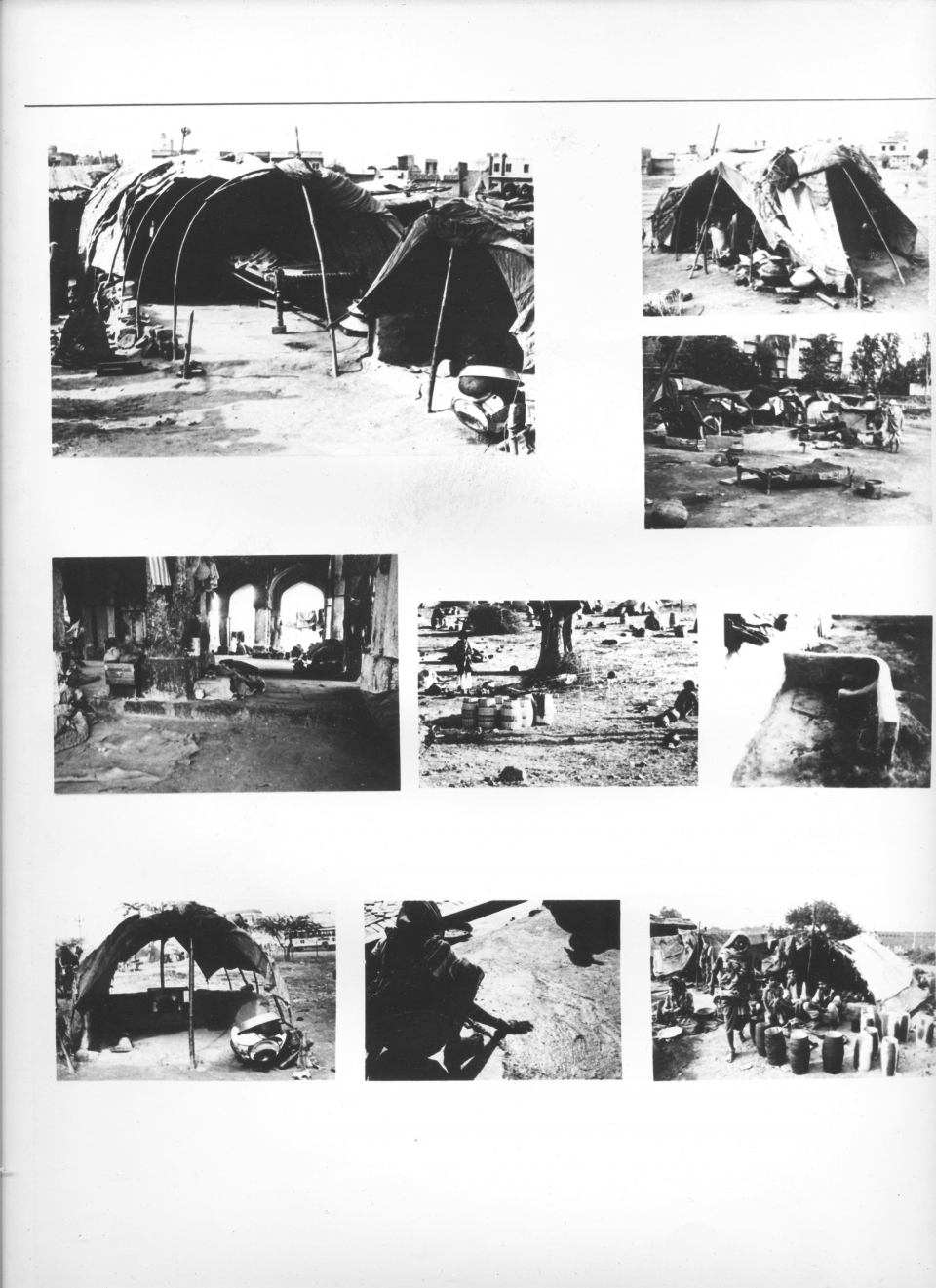

To make a secure shelter they have to find places where they can be left undisturbed. They have to locate materials which are lying around and can be picked up at no cost. Instinctive technologies are devised to suit these materials to their needs. One could draw an analogy with the nesting behaviour of birds.

They have to locate these nests at a distance convenient for foraging to the work areas. these nests have to exhibit the same economy in use of space and materials as we find in nature.

In the hierarchy of needs the security of the nest and provision of water become primary concerns. The human needs which are satisfied by these nests are reduced to the barest minimum.

They have as much freedom to build as birds have. But unlike birds, they have a cultural learning which enables them to confer a meaning on this shelter.

This image is embedded in ...

The patterns of use of enclosed space and the related open spaces are functions of the needs as conceived by dwellers. Rural people bring with them their own notions of structuring of space. The gradation of privacy and sociality which emerges from these notions is reflected in the clustering patters of the spontaneous settlements of the poor. The size and nature of these clusters tends instinctively to reach an optimum in terms of their definition of collective needs.

This image is embedded in ...

This image is embedded in ...

Inter spaces in these clusters are used as public spaces as well as private spaces. These uses are conditioned by the social perceptions of the community, climatic necessitites, the physical constraints of space available, and the economic compulsions of their situation. Not having the necessary capital to buy or rent specialised space for rearing of domestic animals, plying of traditional crafts, petty trading, and production of goods in home-industries, the people naturally use their dwellings and adjacent spaces as work areas.

The aspect of collective life which demands a major adaptation from dwellers is waste disposal. This has become a specialised and expensive proposition in urban centres. The limited capacity of the civic system to cope with this problem is compounded by the incapability of the poor to pay for these services.

In spontaneous settlements the poor have shown an ingenuity in devising tentative provisions to deal with waste-disposal at the household-level. Collective level solutions will require the raising of minimum thresholds of community awarenessess and economic investment of societal resources.

This image is embedded in ...

It may be universally accepted that food along with shelter constitute basic necessities for survival. Yet individual differences persist as to the amount of resources that may be allocated to these needs as against other competing methods. The points of trade-off between different perceptions of satisfaction vary from person to person.

Thus even the meagre resources of the poor have alternative uses.

Any real freedom calls for resource distribution in a manner that permits people to allocate resources in terms of their own perception of needs.

The capacity to fashion alternatives for living in terms of differing perceptions presumes an array of resources, not only economic but informational, technological and organisational access to such resources can permit people to fashion individual destinies as well as to change the allocation of values in society.

This image is embedded in ...

The capacity of the hereditary poor to participate in real decision-making has been atrophied to such an extent that they have lost their belief in their own selves and in their ability to change the world around them. But lack of resources may not become a total handicap, if consciousness can be raised.

The poor, still working out the adaptation to an urban life, do not have the necessary environmental support to make an orderly transition. Ironically, the city forces them to re-assert their parochial identities for reasons of social security. In the process their capacity to effectively operate in the urban environment is impaired. They only become victims of the urban mass-culture.

This image is embedded in ...

Hope lies in building organisations for the purpose of articulating their own interests and values. Given the complex processing involved in making effective demands on the city systems, these organisations need expert services of advocates for their cause.

It is in this context that the problem of housing emerges. The reaction of civic authorities to the spontaneous settlements of the poor range from ignoring their existence to outright demolition.

The alternative of resettlement, constrained by the logic of market price of land, leads to sighting of such colonies on the outer edge of the city.

This image is embedded in ...

Market forces ensure the rapid appreciation of even these marginal lands, leading to capitalisation of the allotments. In a sense this becomes an inefficient method of capital transfer from the state to the poor.

This raises the question whether any housing policy can be devised without reference to issues of social change and the allocation of values.

The task is to devise means for a humane existence for the poor.

This image is embedded in ...

Kamath, Revathi, Vasant Kamath, and Members of the Anandgram Community. Anandgram – Squatters Re-Housing Project, Shadipur, New Delhi. Kamath Design Studio + Members of the Anandgram Community, 1983.