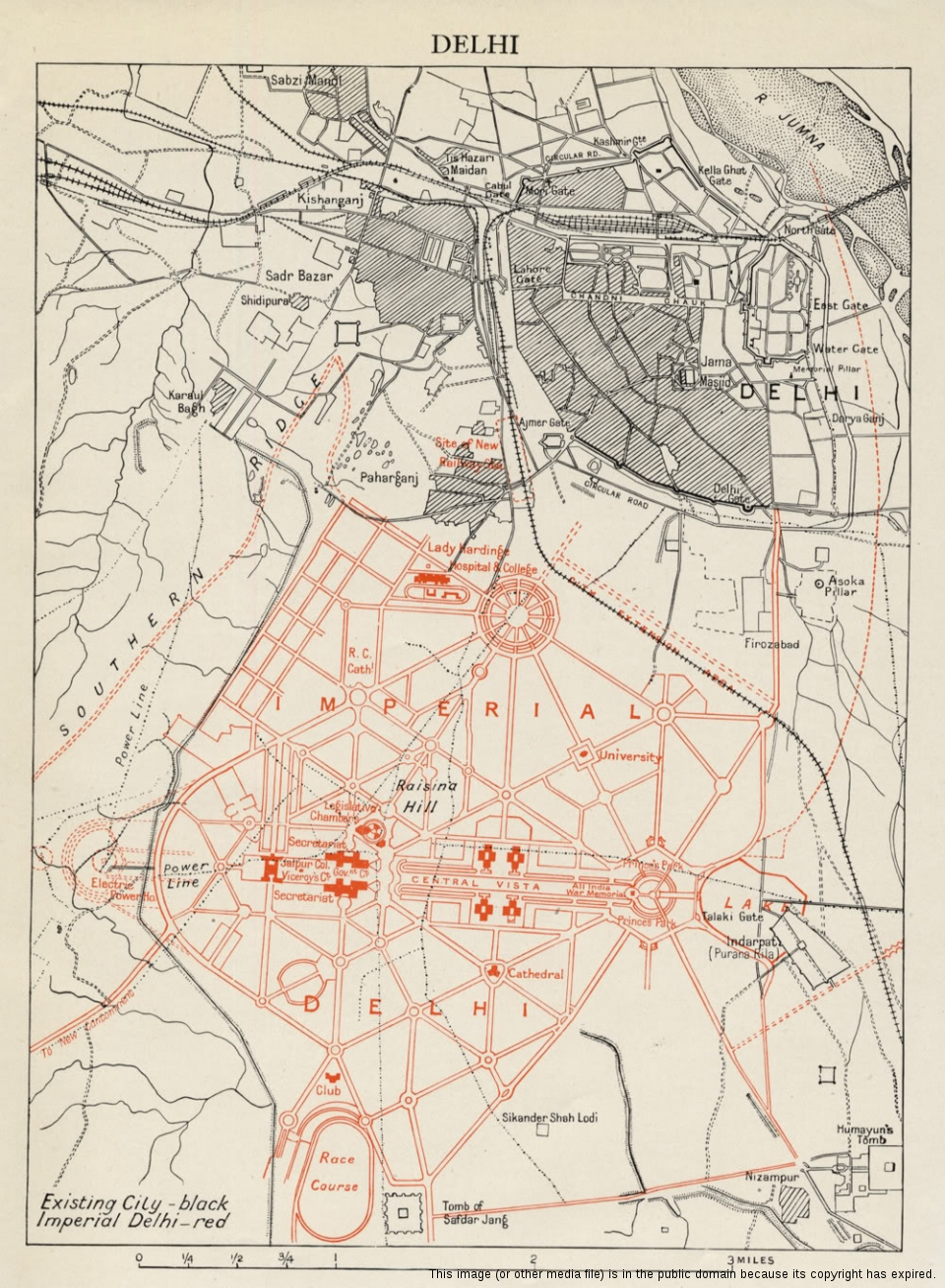

The shift of the capital of British India from Calcutta to Delhi in 1911 necessitated the building of the imperial city of New Delhi. The design of this city and its principal buildings was entrusted to Edwin Lutyens and Herbert Barker, both being architects well versed in the neoclassical tradition flowing from the European renaissance. Their designs were expected to symbolise the grandeur and power of the British Empire as evident at the beginning of the century.

The city layout was finalised by Lutyens in 1915. The plan was derived from the best traditions of the European renaissance and was enlivened by an elaborate design of plantation composed of a carefully chosen varieties of indigenous trees and other vegetation. The buildings and their compounds, as well as the roads, were laid out according to the very generous standards befitting an imperial city.

A great war had broken out in Europe in 1914, and as a consequence the budget for Imperial Delhi was drastically reduced, even before its construction could be started. It is fairly apparent that the architects’ response to the cut in budgetary allocation was reflected in the design of the housing which forms the bulk of the built environment in any city. The public buildings and the overall layout were thus allowed to retain their generous standards, thereby allowing the architects to design one of the grandest ceremonial public spaces of any capital city of the world.

The new capital could not be enjoyed by the British for long, and in 1947 power was transferred to an independent Indian nation. Along with independence came the trauma of partition which brought a sudden increase in the population of Delhi due to the great migration from West Punjab. In the subsequent decades Delhi has grown exponentially to now become a city of nearly 12 million inhabitants. Demographic pressures have resulted in Delhi expanding in all directions encircling the imperial capital designed by Lutyens. The new developments were of high density and built to very different standards as compared to Lutyens’ New Delhi. The contrast between these two sets of standards generated public debate on the need to make modifications to the British imperial legacy.

In 1972 the Ministry of Urban Development constituted the New Delhi Redevelopment Advisory Committee (NDRAC) to propose modifications to Imperial New Delhi. The proposals of the NDRAC, combined with the Master Plan of Delhi of 1960, generated the redevelopment of the area around Connaught Place, the area north of Connaught Place extending up to the walled city, the area around Gole Market, and the multi-storey developments on Prithviraj Road. These developments, however raised considerable public misgivings about their architectural suitability, and in 1988 the area designated as “Lutyens Bungalow Zone” (see map 1) was brought under a virtual development ‘freeze’.

The Lutyens Bungalow Zone covers an area of about 26 sq. km. which constitutes a tiny fraction of the area of Metropolitan Delhi, covering an area of 3179 sq. km. Yet the LBZ area can be characterized as a rare jewel, set at the centre of the complex and chaotic urban framework of the National Capital Region. The LBZ area houses the seat of the national government and incorporates the official residence of: the President of India, the Prime Minister and all other Union ministers, members of Parliament, senior most members of the judiciary, senior most officers of the armed forces and the civil services, as well as housing important national public institutions. Thus, the LBZ area relates not just to the city of Delhi but in a way to the whole Indian nation.

In the last 12 years, while the development restrictions in LBZ have been in force, the anomalies inherent in the urban framework of the LBZ area have become more pronounced. The density of habitation and intensity of building in all areas surrounding the Lutyens Bungalow Zone has increased substantially, thus highlighting the iniquitous nature of the very low density of habitation in the LBZ. The severe restrictions on redevelopment have contributed to isolating the LBZ area from the mainstream of the dynamics of urban growth, thus marginalising the process of maintenance of the physical fabric; which includes the trees planted 70 to 80 years ago, the underground sewerage and drainage system, other services infrastructure like water supply, electricity distribution and telecommunications network, as well as the bungalows built 60 to 70 years ago. Lack of urban maintenance has led to the proliferation of slums in locations not visible, from the main roads. III-considered additions and alterations to the bungalows as well as the public buildings have contributed to the degeneration of the carefully designed physical fabric of the LBZ area. Several inappropriate multi-storied buildings have also come up in this area in spite of the restrictions imposed on such construction.

It is clear that we need a fresh set of planning norms and development controls if the physical environment of the LBZ area is not to degenerate further. In the public debate on the topic of redevelopment norms for LBZ, there are 3 distinct lobbies which have taken up positions. The first is the builders lobby, for which all land is potential for real estate speculation. The second is the conservation lobby which seeks to preserve all buildings designed by the erstwhile imperial architects. The third is the environmental lobby, which sees the LBZ area as a green lung to benefit the entire metropolis of Delhi. There is, however, a fourth point of view which derives from the architectural merit inherent in the design of Imperial Delhi, as in the case of Jaipur and Chandigarh. New Delhi is informed by a singular and powerful architectural vision which confers on its built environment a quality and character, arousing strong feelings in its citizens. As the various lobbies emphasise their own, often conflicting points of view it is clear that the mediating view can best be architectural merit, thus ensuring continuity of the inspirational quality of the design.

While doing a diagnostic survey of Lutyens Bungalow Zone it became apparent that the entire area does not have a uniform architectural character. An analysis of the characteristics of land within the zone reveals 6 types (as shown on map 2).

- Land which is public green and forest.

- Land in use for public institutions, including government and other public offices, cultural institutions, hotels, and protected historic monument.

- Land under government residences (bungalows and other types).

- Land leased for private residences.

- Land for markets.

- Land under barracks/hutments of temporary construction.

Certain areas outside but contiguous with the LBZ boundary are also significant since they have a direct bearing on the redevelopment within the LBZ area. These are: the area north of Ashoka Road and Feroz Shah Road up to and including Connaught Place, the area east of Mathura Road up to the river Yamuna and including the Purana Qila. Pragati Maidan and the zoological park; and the area south of Lodi Road, including the newly-developed institutional area as well as Lodi Colony.

The land characteristics analysis helps to define certain sub-zones within the LBZ which have similar developmental characteristics. The definition is founded on the proposition that the ordering principles of Lutyens’ plan should be retained in their essence and form the basis for any redevelopment strategy. The core of Lutyens’s layout is the Central Vista along Rajpath, with the Presidents Estate on one end and at the other end the public garden framed by the great hexagon of road, with the National Stadium and the Purana Qila forming the termination of the ceremonial axis. This forms a most imposing and attractive public space which makes New Delhi unique among the capital cities of the world.

Extending from the Central Vista is the hexagonal road pattern, which spreads north and south of Rajpath distributing traffic on shady avenues lined with regular plantation of indigenous trees. The Lutyens plan for north of Rajpath originally extended up to the walled city (Asaf Ali Road), but redevelopment exercises of the last two decades have completely changed the character of this area, and now the LBZ boundary has receded to Ashoka Road and Feroz Shah Road, while also including the Bengali Market area bounded by Tolstoy Marg, Barakhamba Road, Sikandra Road and the railway line.

The area south of Rajpath is, in substantial part, a good representation of Lutyens’ architectural vision. The majority of the bungalows in use as official residences are located here, with Akbar Road serving as the principal axis of this part of the LBZ. It should however be noted that the bungalows of Lutyens’ layout extend south only up to Prithviraj Road and Safdarjang Road South of Prithviraj Road and on the south-eastern side adjoining the erstwhile princely states’ houses there are also government residences, but these were designed and built after 1947.

An important feature which this analysis highlights is the presence of major public green open areas on three sides of the LBZ. These are the Delhi Ridge on the west adjoining the Presidents Estate; the connected green of Nehru Park, the Race Course and the Delhi Gymkhana Club, Safdarjang airport, Safdarjang Tomb, and the almost contiguous Lodi Garden on the south; the Delhi Golf Club on the south-east, and on the eastern side across the LBZ boundary along Mathura Road is the large green expanse of the Zoological Garden, with the Purana Qila at one end and Humayun Tomb at the other. This resource of green areas is the most valuable asset, not only of the LBZ but of the entire city of Delhi, because of the fresh air and natural beauty that the green areas represented.

We can thus identify four sub-zones within the Lutyens Bungalow Zone. As shown on map 3 these are:

- Sub-zone grade 1, where architectural and landscape restoration is indicated. This sub-zone includes the public greens of the Delhi Ridge and other open areas described in the analysis above; it also includes the Presidents Estate, the Central Vista, Princes Park, and extends south to include Teen Murti House and bungalows up to the Gymkhana Club, as well as the bungalows between Akbar Road and the Central Vista. This area contains the finest examples of the imperial architecture of Lutyens, and this needs to be maintained in its original form to serve as a heritage treasure house – almost as a living museum.

- Sub-zone grade 2, which extends south of Akbar Road up to Safdarjung Road and part of Prithviraj Road, which has the imperial bungalows still in use, and which requires a special set of development norms. The bungalows here occupy 2 to 3 acres of land each. Their gardens as well as buildings are difficult and expensive to maintain, and the service areas behind these plots have degenerated into slums. This area requires an exercise in ‘conservative surgery’ to restore environmental coherence.

- Sub-zone grade 3, which includes government and private residential development done post-Lutyens, or where substantial redevelopment has already taken place, and the commercial area of Khan Market as well as the institutional area in Lodi Estate having several high schools and a complex of cultural institutions. This sub-zone requires norms which would allow for sensitive redevelopment in keeping with the overall character of the LBZ.

- Sub-zone grade 4 would be the remainder of the LBZ area around Bengali Market, bounded by Sikandra Road, part of Barakhamba Road, Tolstoy Marg, and the railway line. This area has architectural characteristics which are quite different from the rest of the LBZ.

The four sub-zones would each have a specific development strategy; restoration for grade 1, conservative surgery for grade 2, sensitive redevelopment after detailed urban design exercises for grade 3, and redevelopment according to MPD-2001 norms for grade 4.

A major strategic initiative is required for rationalizing the vehicular traffic through the Lutyens Bungalow Zone. The heaviest traffic load in this area is generated by the commuters to the Central Secretariat and other government offices along Rajpath. This commuter traffic is carried largely by diesel-engine buses of the Delhi Transport Corporation supplemented by a very large number of private contract buses and private vehicles. This traffic now poses an environmental hazard and needs to be rationalised to reduce its adverse impact. The existing pattern of bus routes and the location of the major bus terminals are not in consonance with with the spatial logic of the Lutyens plan. It is possible to modify the bus routes so that the Central Vista is relieved of major bus commuter traffic, and the heavy commuter traffic coming in from south of the Central Secretariat does not pass through the heart of the government bungalows on Tughlak Road, Krishna Menon Marg, Akbar Road and Janpath. The major bus terminals can be relocated and distributed on four sides of the government office complex stretching from Raisina Hill to Janpath, which includes the North and South Blocks and the ministry buildings like Shastri Bhawan, Nirman Bhawan etc. Two new terminals need to be located on Janpath, north and south of Rajpath, which could also become interchange points with the proposed mass rapid transit system for Delhi, now under implementation. The new terminals could be a modal shift to a more environment-friendly vehicle type, using solar or electric power.

Since the LBZ is at the centre of the Delhi metropolitan area, there is a tendency for cross traffic to use roads within LBZ as a thoroughfare, resulting in unnecessary environmental stress. The spatial logic of Lutyens plan is generated in large measure by the alignment of Rajpath and Janpath. A third important axis is formed at present by Akbar Road, which connects India Gate to the Race Course Road and Teen Murti roundabout which is an apex of the area where the Prime Minister’s residence is located. It is possible to regulate the high volume intra-city traffic to bypass LBZ on roads which can be renovated according to traffic engineering principles, promoting safety and efficiency. The cross-sections of these roads can be redesigned within the existing right-of-way to improve the flow, speed, and direction of traffic by redesign of the junctions and road surfaces. The reconfiguration of high volume traffic will enhance the environmental quality along the three principal axes of Lutyens’ New Delhi.

The above prognosis emerged out of the study done by the author as a member of the committee appointed in May 1998 by the Ministry of Urban Development to recommend redevelopment norms for Lutyens Bungalow Zone. There were also some specific recommendations which may be of interest to readers, as follows:

- The area bounded by Teen Murti Marg, Race Course Road, and Kushak Nallah be developed as the Vice President’s and Prime Minister’s Estate, with the existing Jawaharlal Nehru Museum in Teen Muriti House being retained. As a consequence, the existing Vice-President’s House on 6 Maulana Azad Road is to be relocated. The new VP & PM Estate proposed has a land area of 33 Ha, out of which Teen Murti House with its grounds occupies an area of 11 Ha. On the remaining 22 Ha a comprehensive redesign exercise may be undertaken to fulfil the present and future requirements of the two State residences along with their associated outbuildings.

- No new office buildings are to be built along Rajpath and Vijay Chowk. The vacant plot opposite the National Museum on the crossing of Janpath and Maulana Azad Road is to be reserved for a cultural institution of national importance, as was originally conceived in the Lutyens plan. The efforts at present to locate the External Affairs Ministry’s office building on this plot will be immediately stopped. Similarly, the efforts to locate the new Naval Headquarters on the southern end of Vijay Chowk are to be continued.

- The erstwhile Princes Park around India Gate and the C-Hexagon, which was designed by Lutyens as the termination of the Central Vista, are to be restored as public gardens dedicated to the people of India and designed around themes of national significance. The National Stadium is to be renovated for use as a venue for state functions. The area around the stadium can be cleared of the the temporary barracks/hutments, and the land suitably landscaped as recreational area around the stadium.

- Detailed technical studies are required to be conducted in order to ensure that redevelopment within the LBZ is framed according to the highest standards of environmental planning, traffic engineering, and architectural design befitting the national capital.

- A Special Area Management Agency be constituted to regulate and monitor the redevelopment within the LBZ. Such an agency would necessarily need to have a level of autonomy, such that its functioning is legally binding and independent of the various local authorities which presently exercise administrative and planning jurisdiction in the Lutyens Bungalow Zone

It is hoped that the Ministry of Urban Development is able to benefit from the public debate on the issues emerging from the need to redevelop Lutyens Bungalow Zone. As the capital city, Delhi inevitably becomes a model for the rest of the country, and any redevelopment exercise here will set trends to influence urban reconstruction in India in the years to come.