An exhibition at Tate Liverpool reveals an artist whose quest for utopian design and universal forms has placed her as a modern master.

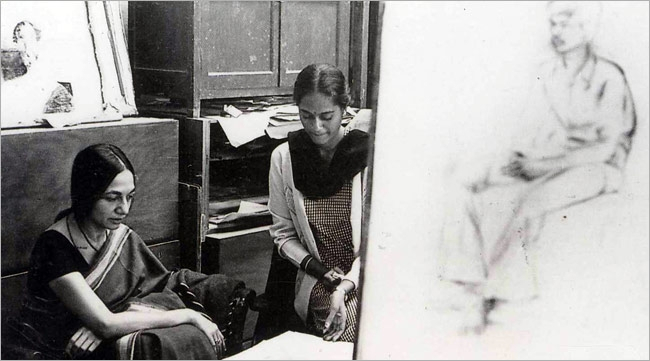

Nasreen Mohamedi’s is an intriguing world. Abstract pencil lines and geometric patterns float in the vacuity of a piece of paper. On others, complex yet organic structures weaving against each other create an illusionary universe, giving a sense of the artist’s obscure inner dialogue. Undated and untitled, and 24 years after her death, Mohamedi’s drawings still leave a viewer unsettled. Recent years have seen efforts to unravel the mystery behind the late artist — notably, solos at Milton Keynes Gallery (UK, 2009) and Talwar Gallery (New York, 2008), and a retrospective at Kiran Nadar Museum of Art (Delhi, 2013). On June 6, an exhibition at Tate Liverpool titled “Nasreen Mohamedi” will be the biggest solo of the artist in the UK, which will span her work from the ’60s to the ’80s.

There are over 60 works on display, acquired from various public institutions and private collections. The exhibition has been curated by Eleanor Clayton, assistant curator at the Tate Liverpool, who started exploring Mohamedi’s oeuvre when she was putting together Dutch artist Piet Mondrian’s work for the gallery (it will open simultaneously with Mohamedi’s show). “I grew obsessed with her intricate line drawings and earlier oil paintings, particularly in conjunction with her diaries, which reveal a constant quest for utopian design and balance in her work,” says Clayton, “Although Nasreen and I come from different places and times, learning about her work has made me view the world in a new way, seeing the abstract and universal beauty she focused on landscapes, from India to the Mersey river.”

....

While her line drawings are the most popular aspect of her oeuvre, what is also fascinating is Mohamedi’s photographic prints, known for their unique architectural quality. A well-travelled artist, Mohamedi took photographs in several places in the Middle East (she lived in Bahrain briefly in her youth), the US and Japan, apart from various cities in India including Chandigarh. For Clayton, her photographs, which highlight geometric shapes and lines in her surroundings through particular crops, mirrored how Mondrian began his path to abstraction, a reason why the two exhibitions will open simultaneously.

Another significant aspect is Mohamedi’s diaries, which reveals the artist’s mind at work. On display at Tate Liverpool are extracts, notes and source material she kept in her studio.