[A] project has resulted in two scientific articles, the last one just been published. They can both be found in the journal Heritage Science:

"We have discovered no less than two pigments whose use in Antiquity has hitherto been completely unknown," says Kaare Lund Rasmussen.

These are lead-antimonate yellow and lead-tin yellow. Both are naturally occurring mineral pigments.

"We do not know whether the two pigments were commonly available or rare. Future chemical studies of other antiquity artefacts may shed more light," he says.1

- 1. Lead-antimonate yellow and lead-tin yellow have so far only been found in paintings dating to the Middle Ages or younger than that. The oldest known use of lead-tin yellow is in European paintings from ca. 1300 AD. The oldest known use of lead-antimonate yellow is from the beginning of the 16th century AD. Analyzing binders is more difficult than analyzing pigments. Pigments are inorganic and do not deteriorate as easily as most binders which are organic and therefore deteriorate faster. Nevertheless, Kaare Lund Rasmussen's Italian colleagues from Professor Maria Perla Colombini's research group at the University of Pisa managed to find traces of two binders, namely rubber and animal glue.

Signe Buccarella Hedegaard, Thomas Delbey, Cecilie Brøns, Kaare Lund Rasmussen. Painting the Palace of Apries II: ancient pigments of the reliefs from the Palace of Apries, Lower Egypt. Heritage Science, 2019; 7 (1)

DOI: 10.1186/s40494-019-0296-4

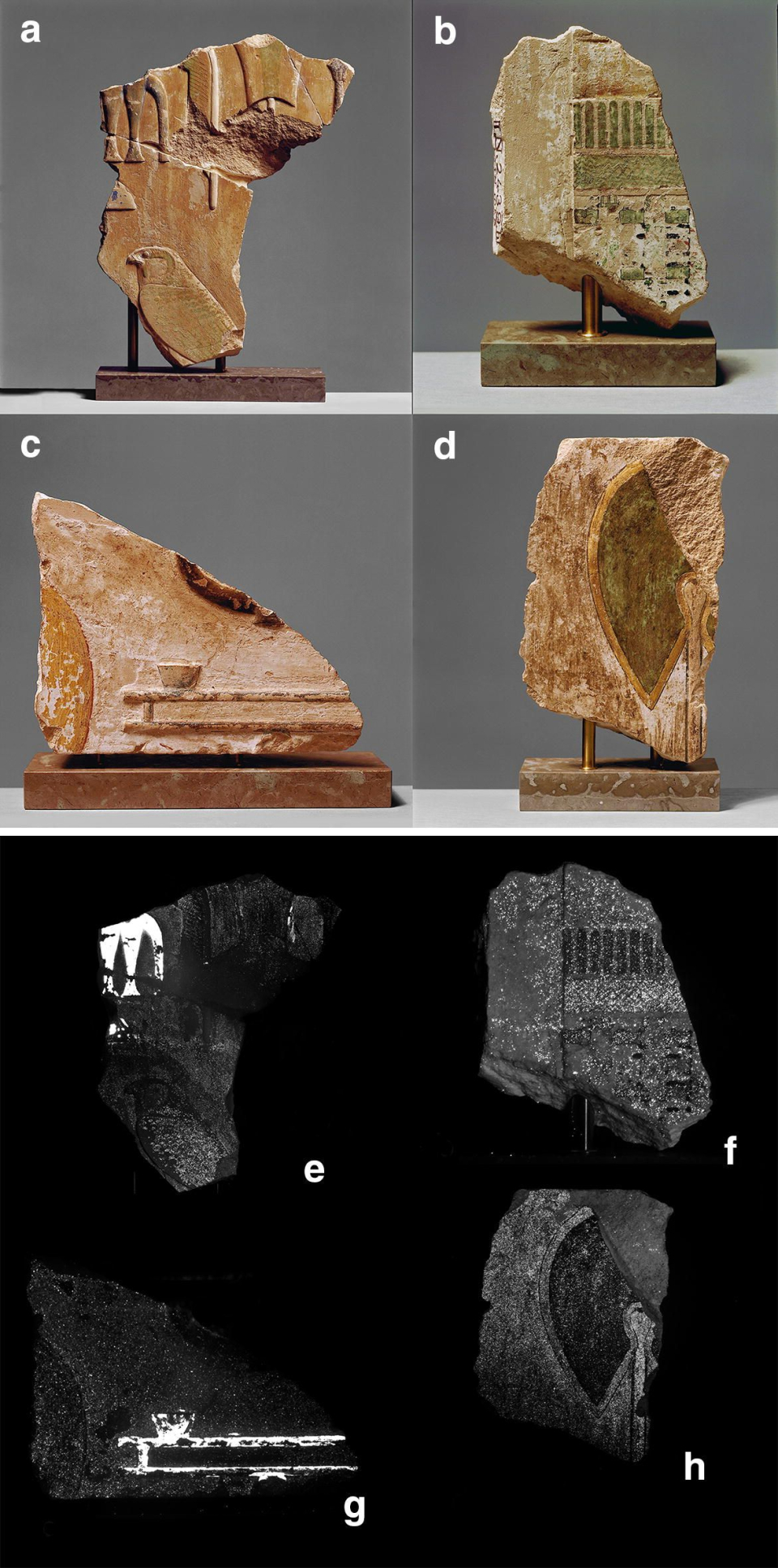

Fragments of painted limestone reliefs from the Palace of Apries in Upper Egypt excavated by Flinders Petrie in 1908–1910 have been investigated using visible-induced luminescence imaging, micro X-ray fluorescence, laser ablation inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry, micro X-ray powder diffraction, and Fourier transform infrared spectrometry. The pigments have been mapped, and the use and previous reports of use of pigments are discussed. Mainly lead–antimonate yellow, lead–tin yellow, orpiment, atacamite, gypsum/anhydrite, and Egyptian blue have been detected. It is the first time that lead–antimonate yellow and lead–tin yellow have been identified in ancient Egyptian painting. In fact, this is the earliest examples known of both of these yellow pigments in the world.

Cecilie Brøns, Kaare Lund Rasmussen, Marta Melchiorre Di Crescenzo, Rebecca Stacey, Anna Lluveras-Tenorio. Painting the Palace of Apries I: ancient binding media and coatings of the reliefs from the Palace of Apries, Lower Egypt. Heritage Science, 2018; 6 (1)

DOI: 10.1186/s40494-018-0170-9

This study gives an account of the organic components (binders and coatings) found in the polychromy of some fragmented architectural reliefs from the Palace of Apries in Memphis, Egypt (26th Dynasty, ca. 589-568 BCE). A column capital and five relief fragments from the collections of the Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek in Copenhagen were chosen for examination, selected because of their well-preserved polychromy. Samples from the fragments were first investigated using Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy to screen for the presence of organic materials and to identify the chemical family to which these materials belong (proteinaceous, polysaccharides or lipid). Only the samples showing the potential presence of organic binder residues were further investigated using gas chromatography with mass spectrometry detection (GC–MS) targeting the analysis towards the detection and identification of compounds belonging to the chemical families identified by FTIR. The detection of polysaccharides in the paint layers on the capital and on two of the fragments indicates the use of plant gums as binding media. The interpretation of the sugar profiles was not straightforward so botanical classification was only possible for one fragment where the results of analysis seem to point to gum arabic. The sample from the same fragment was found to contain animal glue and a second protein material (possibly egg). While the presence of animal glue is probably ascribable to the binder used for the ground layer, the second protein indicates that either the paint layer was bound in a mixture of different binding materials or that the paint layer, bound in a plant gum, was then coated with a proteinaceous material. The surface of two of the investigated samples was partially covered by translucent waxy materials that were identified as a synthetic wax (applied during old conservation treatments) and as beeswax, respectively. It is possible that the beeswax is of ancient origin, selectively applied on yellow areas in order to create a certain glossiness or highlight specific elements.