....

Choose your definition.

Even as you choose, know this. That edifice which looks so imposing, those rows of books which look so welcoming, they are as susceptible to the passage of time as you are. Time ravages books just as much as silverfish, mildew and blades wielded in secret and in silence. The book has many enemies. So have libraries.

But the worst enemy of all is the sound of receding footsteps, as people walk away from libraries. Tell me, when did you last go to the library?”

– Jerry Pinto

Jerry Pinto1 brought me back to books. My footsteps, too, had receded several years ago, but it was Jerry who urged me to wander back into my dream space, and rediscover my personal library, that ever increasing tower of paper, that initially would stare at me, and make large, forlorn puppy-dog eyes: hey, why aren’t you spending time with me, later, would glare at my continued indifference, photography, life and other excuses having taken over, and then, eventually, those books would only sigh, resigned to my cold shoulder.

I met him for the first time only recently, to indulgently get my books signed (some for me, and some for a fellow Pintoian). But I met him a few years ago, when I met his mother, Em. His book, Em and the Big Hoom, brought me back to books. It was that one spark that did restart the fire.

Chirodeep Chaudhuri2 was the first photographer I ever met, aside from my professor/mentor/friend, David de Souza. His photos caught my attention because he seemed to share a common love, Bombay.

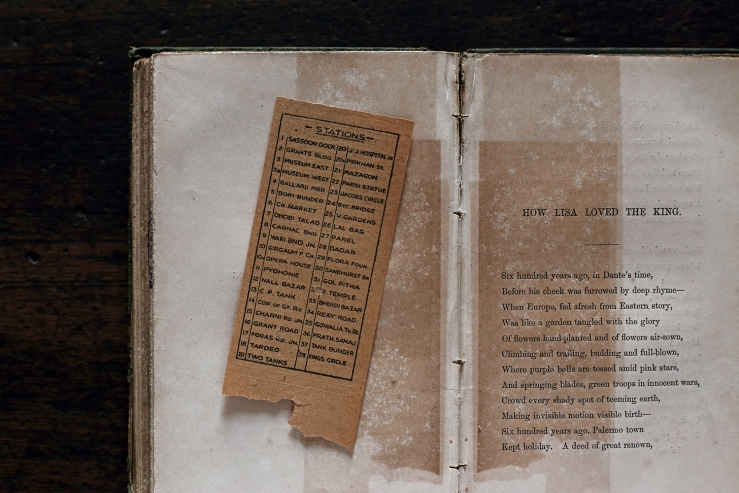

Pinto & Chaudhuri have, together, coauthored an exhibition that is currently showing at Project 88, in the heart of Colaba in Bombay. ‘In the City, a Library’ is their collaborative documentation of the People’s Free Reading Room & Library, an iconic institution that dates back to 1845.

....

- 1. Jerry Pinto is a writer who lives and works in Mumbai. He is the author of Em and the Big Hoom, which won the Hindu Lit for Life Award, the Crossword Prize for Fiction, The Windham-Campbell Award administered by the Beinicke Library of Yale University, USA and the Sahitya Akademi award for a novel in English. He teaches journalism at SCM Sophia and serves on the boards of several organisations.

- 2. Chirodeep Chaudhuri is the author of the critically acclaimed book ‘A Village In Bengal: Photographs and an Essay”, a result of his 13-year long-engagement with his ancestral village in West Bengal; India and his family’s nearly two century old tradition of the Durga Puja. His most recent book “With Great Truth & Regard: The Story of the Typewriter in India” documents the history of the manual typewriter in India. Chirodeep’s work documents the urban landscape and during his more than two-decade-long career he has produced diverse documents of his home city in a range of projects like ‘Bombay Clocks’, ‘The One-Rupee Entrepreneur’ and ‘The Commuters’ among others. His work has been featured in some of the most important publications about Bombay.He lives in Bombay dividing his time between a deepening engagement with image making and teaching assignments.

....

- You have discussed the idea of photographing something to do with reading before? Was this around the time you were photographing The Commuters? I remember, there was a tiny stream within those photos, that had sets of people in the train poring into their newspapers, something that you had once referred to as your ‘interest in tabloid visual culture’.

Chiro: There is always a lot of tangential reading and thinking that one is doing, and it is these peripheral thoughts that keep redefining the way you may look at a certain idea. I had come across a rather lovely essay on the origins of tabloid newspapers, and how it coincided with the courtesies of commuting in the NYC subway, a thought that immediately reminded me of our trains, and how every inch matters. Imagine opening a broadsheet like The Indian Express in the local. This made me start noticing a lot of tabloids around, so yes, some of them did creep into my photos of that time.

Meanwhile, however, Anil Dharker was due to launch the Literature Live festival, and Jerry asked me if I would be interested in photographing a series on people reading, for a book that the festival was planning. I gave this some thought and realised that I was a little uneasy with the idea. Lit fests are happening as a counter to the fact that people aren’t reading, so if I do ten pictures of people with books, in different spots around the city, I think it is a disconnect, these are two opposite things we are talking about. But this was the starting point, of trying to engage with the idea of photographing the issue that there is a drop in reading, a vacuum in this cultural activity.

This was also the time when those Mayawati statues were coming up, and I remember being struck by the fact that here is this person, constructing these huge statues of herself, holding a handbag. I thought that was rather weird. Now, I had been looking at Bombay’s architecture for a long time, and the statues that are a part of this architecture have almost always had the luminary carrying a book. Whether it is Phirozshah Mehta or Dadabhai Naoroji, or even Ambedkar, they are often depicted, with a book. So what does that tell you? That at a certain point in the city’s history, any city’s history, books mattered. Intellect had value. I cannot think of any political leader today whose statue you can think of, with a book. So as all these things tumbled out of the mental archive, you start to connect the dots. That the statues while being relics of time, were also, a sign of the times. I eventually did those photos for Time Out Mumbai. So what started as Jerry’s germ of an idea, of doing a series on people reading, eventually became our shared lament, of people not reading.

- The way you describe these statues almost suggests that an integral history of Bombay, or of any city, is connected to the dissemination of knowledge, to public libraries, to reading. How does that stand today?

Chiro: No, I wouldn’t connect it with Bombay specifically. That would be a bit of a stretch and a little unfair to other cities. It is just that there was a certain time in history when intellect seemed to matter, as opposed to today, when it has almost become a bad word. To be liberal or to be intellectual are qualities that are almost derided now. At a time when money seems to talk louder, a Mayawati statue with a handbag is only a reflection of our shifting values.

Those were also quieter times. And reading is intrinsically linked to quiet, to contemplation, to slowness. In Bombay, people were always running, but today, they seem to be scurrying a whole lot more. The kind of narrative that seems to exist today is that people’s attention spans are less, so we need to give them snippety stuff. This infotainment nonsense. Obviously that goes against the basic grain of reading. And when newspapers and magazines, disseminators of the written word, themselves seem to not believe in the power of words anymore, what can one say?

- What I meant by connecting it to the city is the fact that I’d often see books within the urban landscape earlier, and now, it is the ubiquitous screen. If one can say that a city is defined by what it reads, today, it can be defined by whether it reads. Merely a decade ago, my impressions of the person sitting in front of would be based on what he or she is reading, you know the cliche idea of spotting a girl in the train who happens to be reading your favourite book.

Chiro: I generally have this habit of looking at people’s bookshelves, or even their bedside tables, for that matter. I think it gives you a lot of insight into who they are. But while on our lament of people reading less, you know, even the people who read have this constant battle with themselves, on all that they haven’t read. The large horde of unread books that we have, but haven’t picked up. I am reminded of another lovely piece of writing by Nassim Nicholas Taleb, on the relationship of the legendary Umberto Eco with his books. Taleb wrote,

“The writer Umberto Eco belongs to that small class of scholars who are encyclopedic, insightful, and nondull. He is the owner of a large personal library (containing thirty thousand books), and separates visitors into two categories: those who react with “Wow! Signore professore dottore Eco, what a library you have! How many of these books have you read?” and the others — a very small minority — who get the point that a private library is not an ego-boosting appendage but a research tool. Read books are far less valuable than unread ones. The library should contain as much of what you do not know as your financial means, mortgage rates, and the currently tight real-estate market allows you to put there. You will accumulate more knowledge and more books as you grow older, and the growing number of unread books on the shelves will look at you menacingly. Indeed, the more you know, the larger the rows of unread books. Let us call this collection of unread books an antilibrary.”

Now, if Umberto Eco can have an antilibrary, maybe we shouldn’t be so harsh on ourselves (for further reference on Taleb’s piece, read this and this).

Going back to your point of the screens within our trainscapes, the transition has been stark. I sometimes think that if I were to photograph The Commuters today, the project would end up being so different. The pictures I had shot, only a few years ago, were of people sitting in front of me, looking at me, looking away. Today, nobody is even looking up…

....

- Who have been your personal favourite chroniclers of Bombay? Whether it is someone who uses words, photos or cinema…

Jerry: I think there are different people for different media. In cinema, there’s Anurag Kashyap and Manmohan Desai. In poetry, Adil Jussawalla, Nissim Ezekiel and Arun Kolatkar. In fiction, Kiran Nagarkar and Shanta Gokhale. In non-fiction, Naresh Fernandes and Suketu Mehta. In photography, Chirodeep Chaudhuri, Ashima Narain, Prashant Nakwe.

Chiro: I really like M S Gopal‘s work. I am a huge fan of his. There are a few times when I look at his photos and think ki thoda dhyaan deta toh it would be even better. But that said, I love the way he sees. You look at his photo and say, oh damn, I wish I had thought of that. And not just what he is seeing, but also how he is connecting. The connecting of the dots, his political awareness. His day job as an advertising fellow makes him look at the city in a certain way, and what comes out, is brilliant. He is the only photographer whose work I actively look out for. Like the thing he did the other day…

…the map?

Chiro: Yeah! I mean, fuck man. You just die of envy when you see something like that (click here to see the photograph being spoken of).