The development of Indian architecture has been influenced by its long history, extremely varied geographical and environmental conditions across the country, and ancient but powerful philosophical ideas originating here. The consequent cultural diversity is exemplified in the form of the towns and cities which have evolved over time across the country.

Against this multi-layered backdrop the realities of present day life pose very special challenges for the development of a contemporary architectural ethos. With a quarter of the country’s population living in cities today, we can identify 3 distint types of urban structure which together constitute the contemporary city. These 3 urban types – the organically evolved, the planned, and the spontaneous – present the challenge of integration to form a harmonious whole, while respecting the cultural characterstics inherent in each type.

The problem of very large numbers in Indian cities poses the challenge of managing scarce resources effectively. Recent advances in industrial development interface with a great repertoire of indigineous crafts and traditional techniques which enrich the building trade. Indian architects have addressed the challenge of rediscovering an architectural idiom appropriate to contemporary conditions with commendable seriousness.

Perhaps the greatest hope lies in the development of a professional ethos which is responsive to these challenges of historical continuity, of scarce resources and large numbers, of socio-cultural complexity and technological contradictions. This would provide the necessary pre-conditions for creating a healthy and civilized urban future.

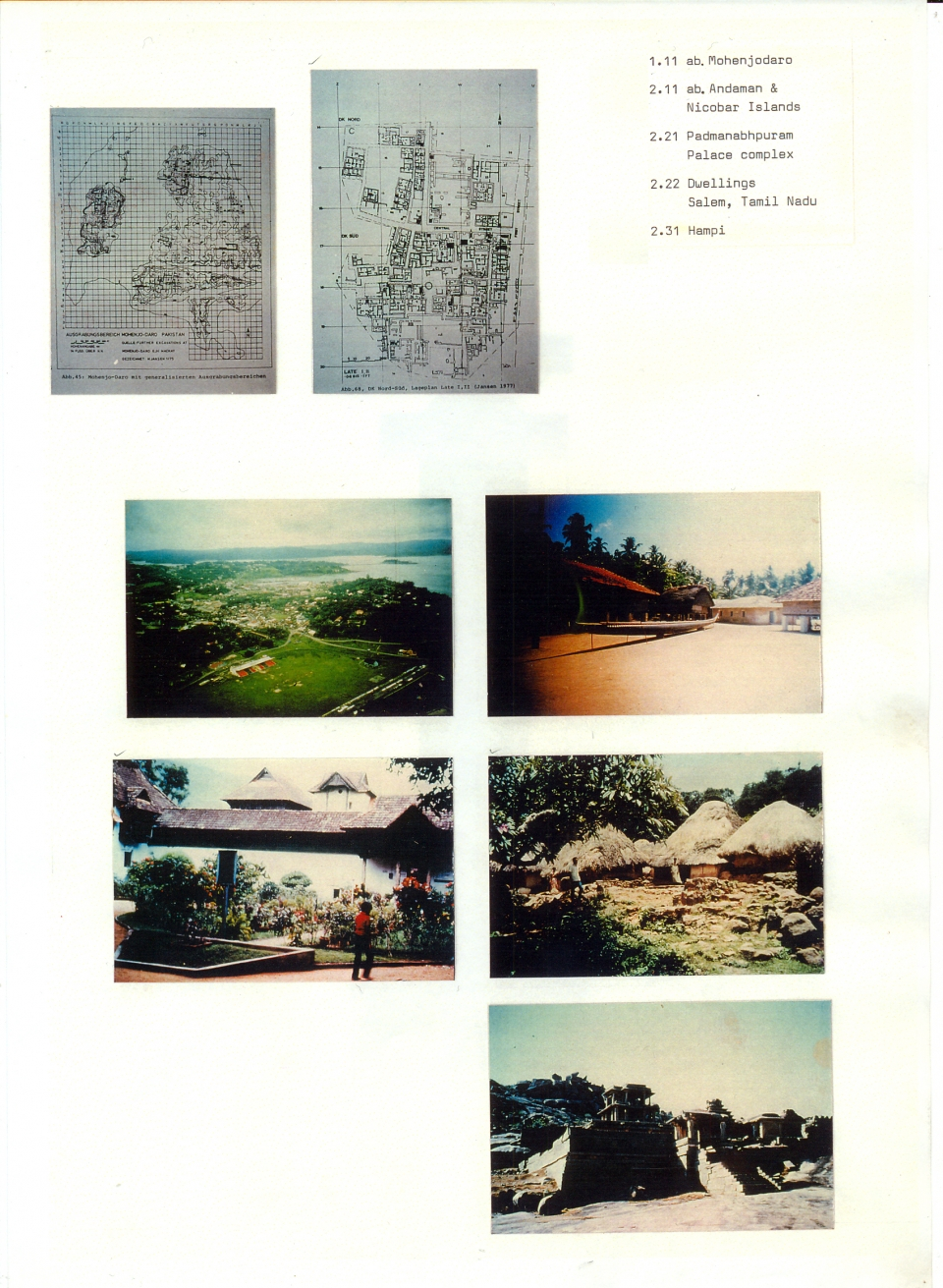

The architecture of the Indian sub-continent has a very long lineage. This extended time span gives us a historical backdrop of monumental dimensions. Archeological evidence of the Indus Valley Civilisation has shown us that well-planned and architecturally cohesive cities existed in the north-western region of this sub-continent as early as 2500

B.C. Excavations at the site of the city of Mohenjodaro reveal a clearly defined urban pattern of major and minor streets, a compactly structured built form suited to the harsh climate of this region, and distinct public buildings set within the residential quarters.

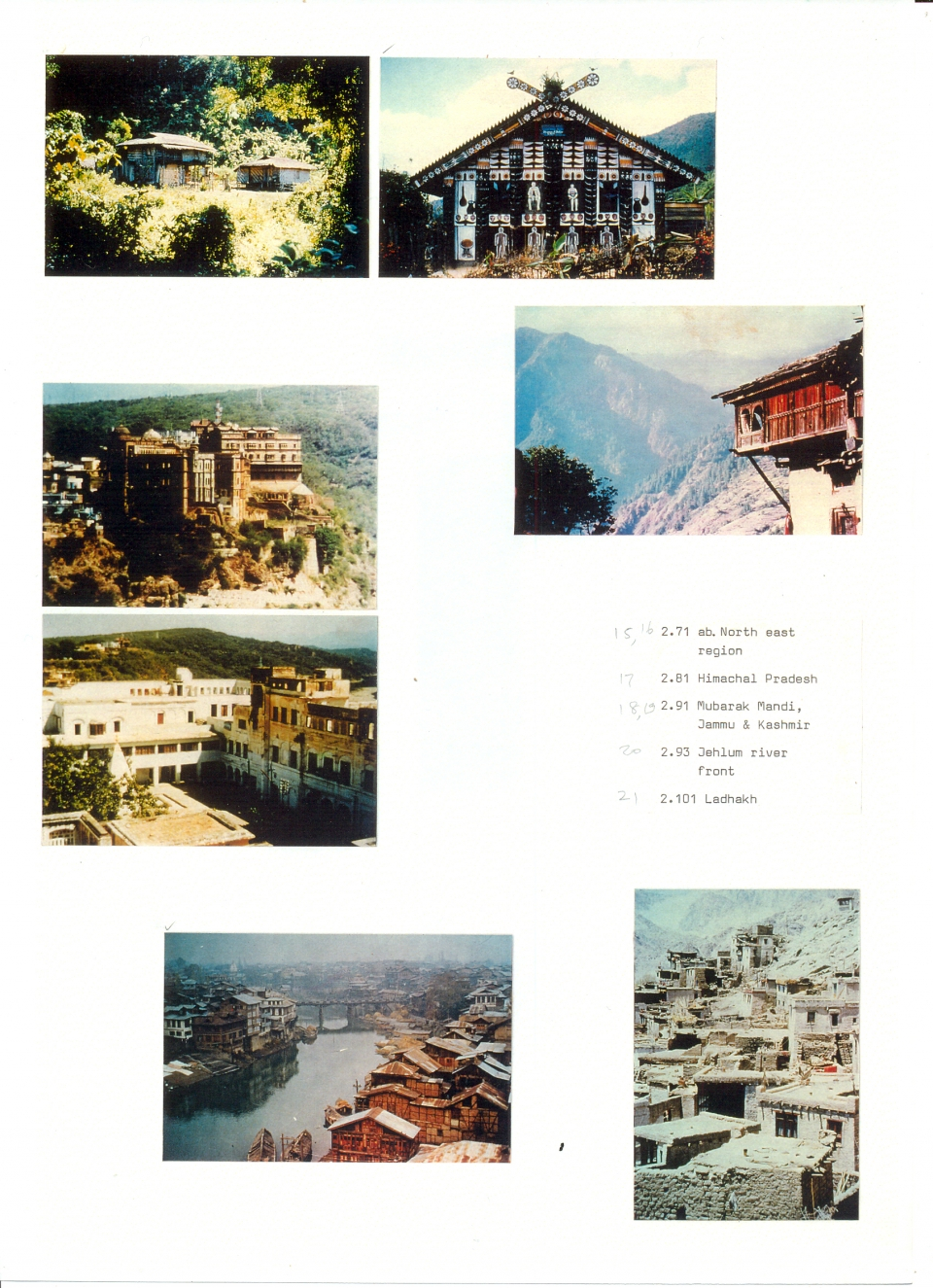

The historical dimension forms only one axis of a description of Indian architecture. Another axis is formed by the variety of land forms and natural resources. The geographical boundaries of India extend over such diverse terrain that an extraordinary spectrum of environmental conditions is covered. These range from the almost equatorial climate of the Andaman and Nicobar islands group in the Indian Ocean2, to the sub- tropical coastal areas of kerala and Tamil Nadu, the plateau regions of the Deccan peninsula, going northwards to Central India, west to the desert region of Rajasthan, the fertile plains of the basins of the Indus and the Ganges river systems, the monsoon-fed forests of the North-East, and the vast mountain regions formed by the Himalayan ranges, which include the picturesque and fertile Kashmir Valley as well as the almost arctic deserts of Ladakh. The architectural responses to this variety of environmental conditions have evolved over time to present a most extensive typology of building forms.

The formal language of Indian architecture is, however at its best, most deeply influenced by the third axis formed by the philosophical tradition. Exemplified by ancient and powerful schools of thought such as Vedanta and Buddhism. Architectural canons for building and town planning were set out very early in several treatises which provide a great reservoir of knowledge instrumental in generating a humane built environment.

Prominent among these treatises is the “Manasara” which dates back to the 5th century A.D.

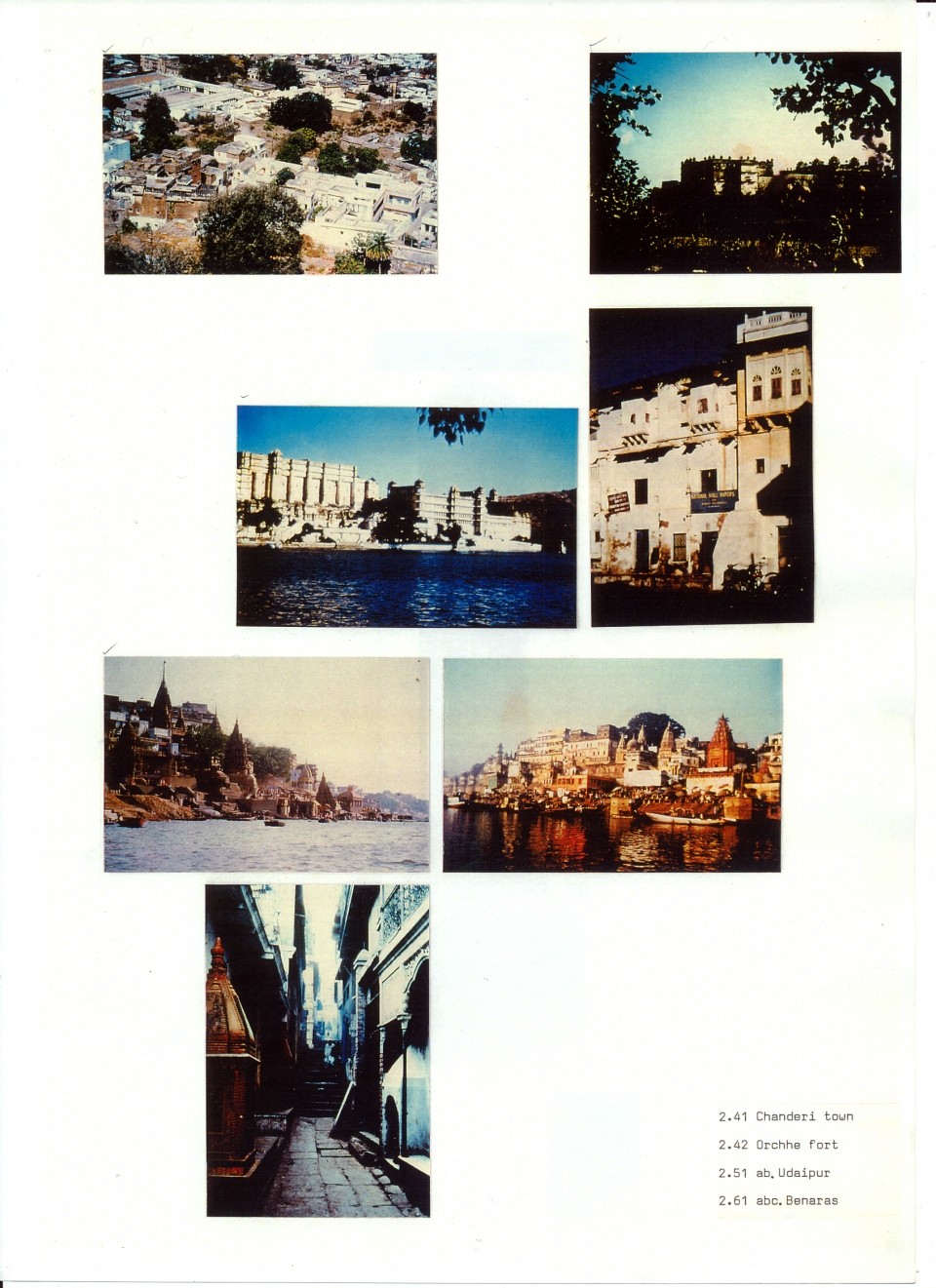

The several factors have resulted in a remarkable cultural diversity, perhaps best exemplified in the form of the various towns and cities which have evolved over time across the country.

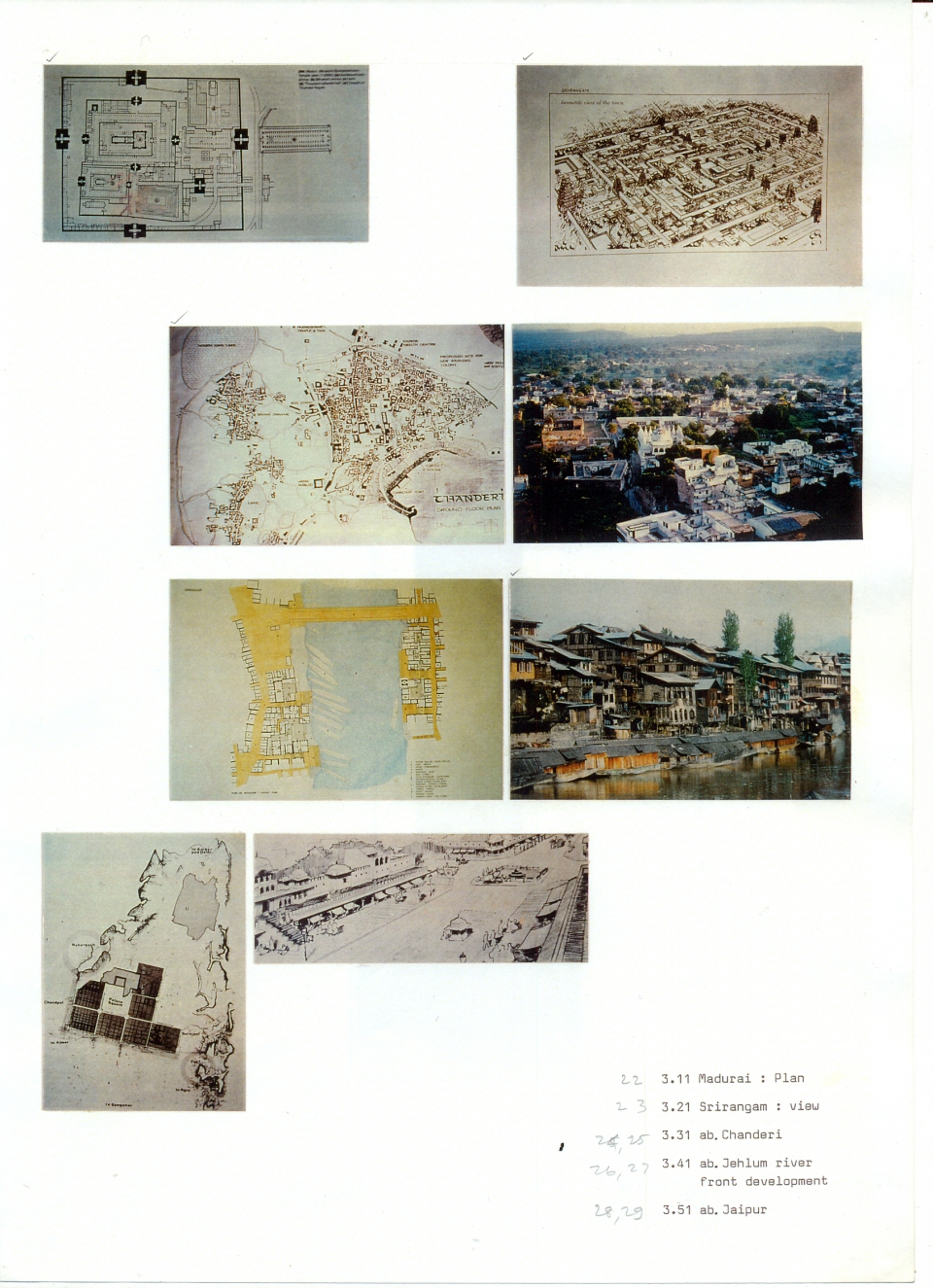

The temple towns of Madurai and Srirangam in South India, in evolution for the last six centuries or so, represent a cosmic vision of hierarchically layered reality; the plan is formed by concentric geometries around defined centres.

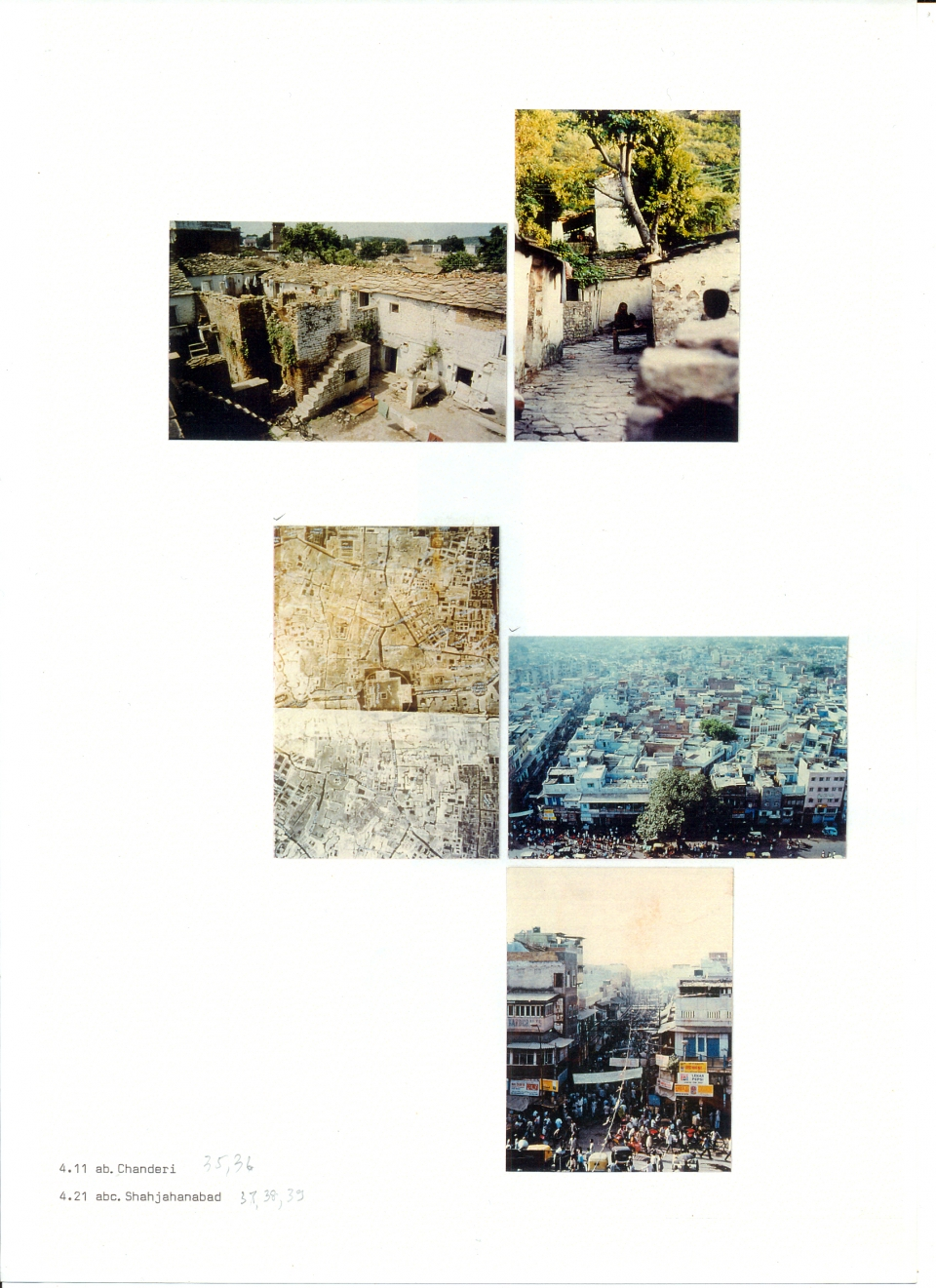

In contrast a more organic pattern can be found in the weaver’s town of Chanderi in Central India. This town, first established in the 15th century A.D., has a plan defined by the natural topography and a social order representative of the broad divisions of caste in medieval Indian society.

A distinctly different architectural language has emerged for the riverbank city of Srinagar in the Kashmir Valley in northern India. The river forms a major transport artery in this valley, and the city has developed mainly over the last 300 years along both its banks, to provide a finely woven and contextually rich urban form on a human scale.

A most significant exercise in city planning in the early part of the 18th century A.D. resulted in the development of the city of Jaipur in Rajasthan, west-central India. The plan for the city is based on a nine-square mandals adapted to take advantage of the natural features of the site. The layout incorporates a

The formal language of Indian architecture is, however at its best, most deeply influenced by the third axis formed by the philosophical tradition. Exemplified by ancient and powerful schools of thought such as Vedanta and Buddhism. Architectural canons for building and town planning were set out very early in several treatises which provide a great reservoir of knowledge instrumental in generating a humane built environment.

Prominent among these treatises is the “Manasara” which dates back to the 5th century A.D.

The several factors have resulted in a remarkable cultural diversity, perhaps best exemplified in the form of the various towns and cities which have evolved over time across the country.

The temple towns of Madurai and Srirangam in South India, in evolution for the last six centuries or so, represent a cosmic vision of hierarchically layered reality; the plan is formed by concentric geometries around defined centres.

In contrast a more organic pattern can be found in the weaver’s town of Chanderi in Central India. This town, first established in the 15th century A.D., has a plan defined by the natural topography and a social order representative of the broad divisions of caste in medieval Indian society.

A distinctly different architectural language has emerged for the riverbank city of Srinagar in the Kashmir Valley in northern India. The river forms a major transport artery in this valley, and the city has developed mainly over the last 300 years along both its banks, to provide a finely woven and contextually rich urban form on a human scale.

A most significant exercise in city planning in the early part of the 18th century A.D. resulted in the development of the city of Jaipur in Rajasthan, west-central India. The plan for the city is based on a nine-square mandals adapted to take advantage of the natural features of the site. The layout incorporates a

Carefully planned water supply and drainage system integrated with the distribution of people and facilities according to a hierarchical street patterning based on social order, climatic considerations, and the overriding concern for a scale suited to the needs of the inhabitants.

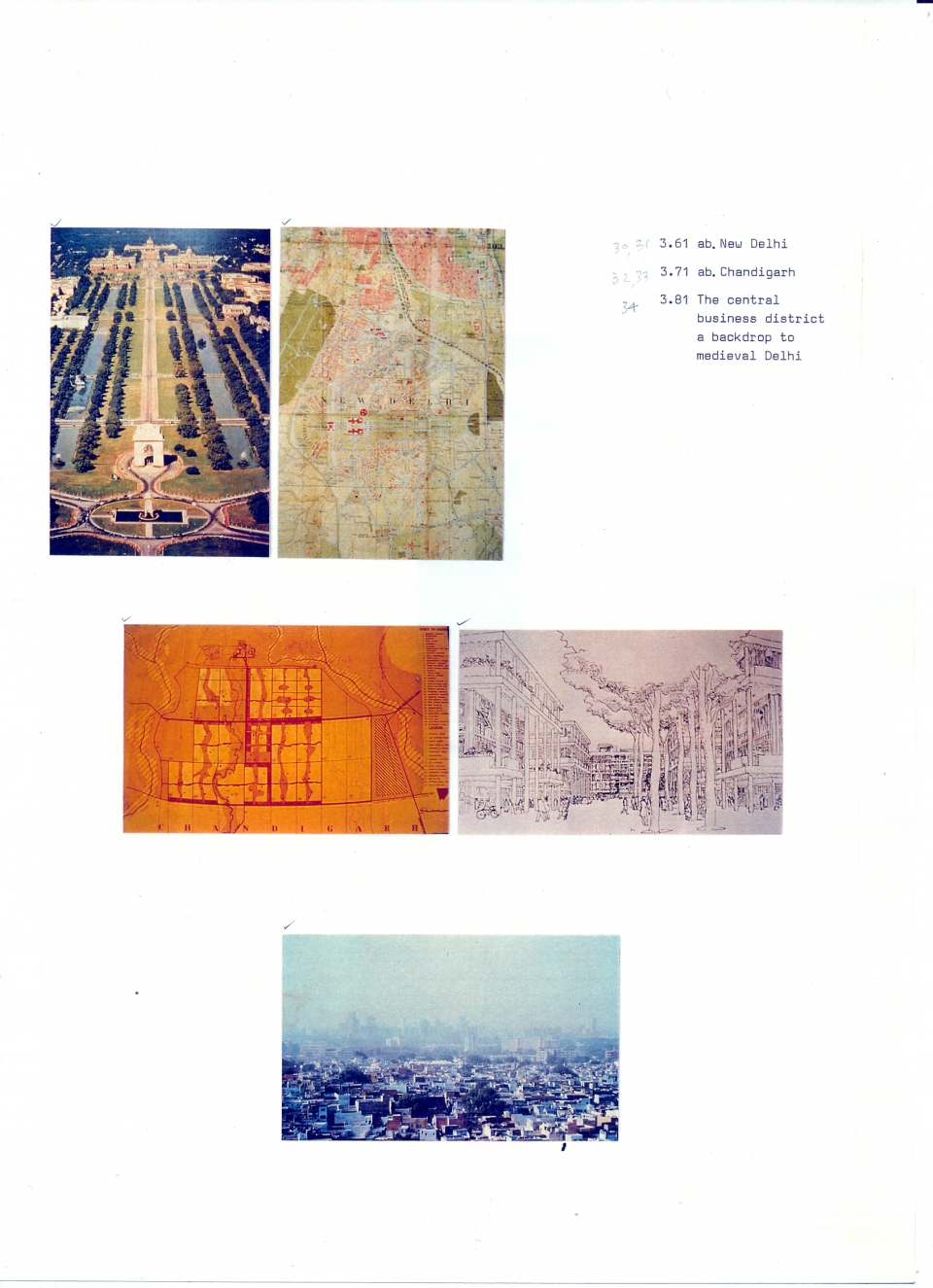

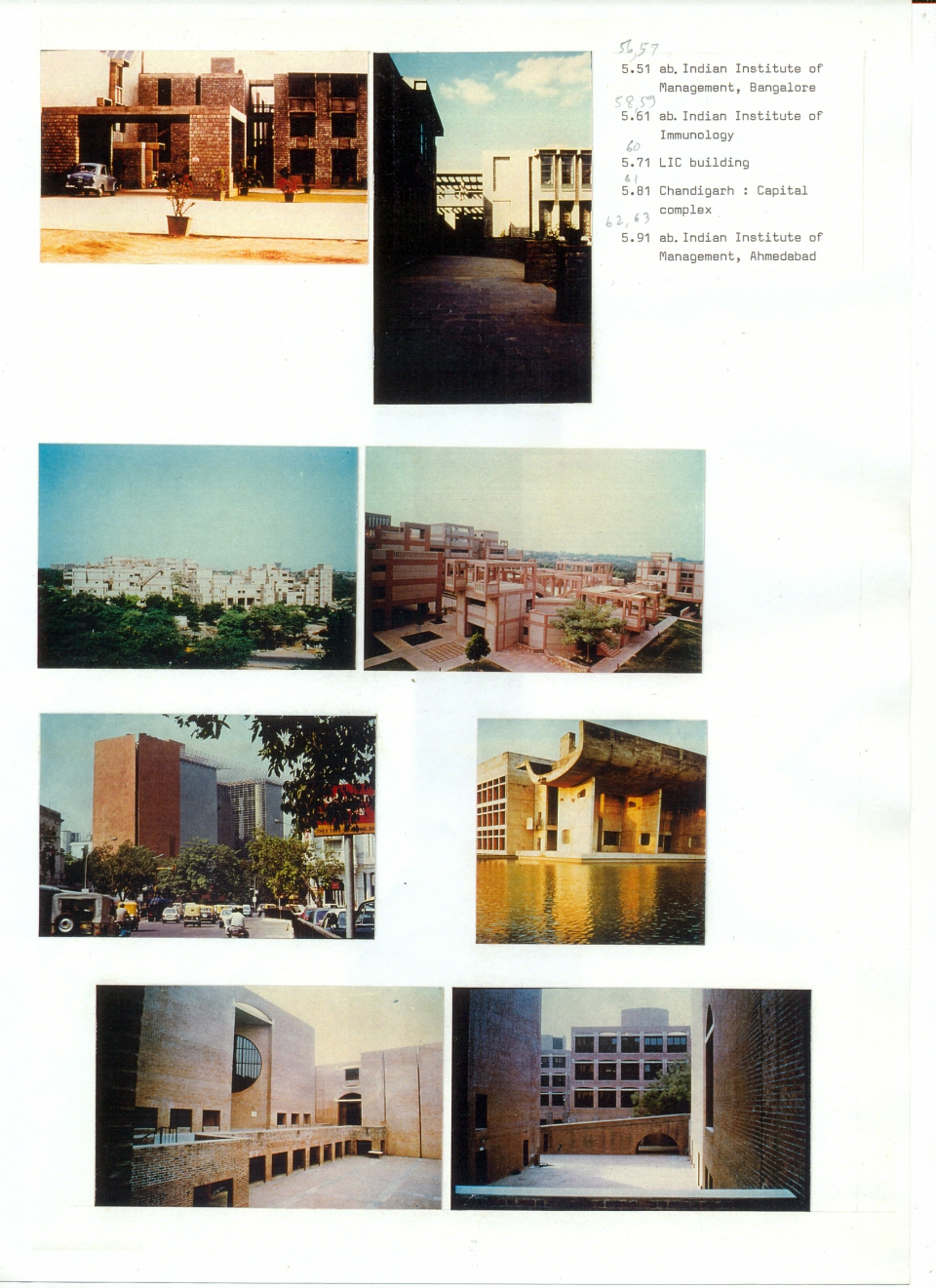

Different from the indigenous city types just mentioned, there are two important examples of European town-planning ideals translated for application in the Indian context in this century. These are the city of New Delhi designed by Sir Edwin Lutyens in the first quarter of this century, and the city of Chandigarh designed by Le Corbusier around the middle of this century. Both these examples have enriched the formal vocabularly of urban design and architecture, thus contributing to the increase of plurality in architectural expression.

Against this multi-layered backdrop the realities of present day life in India pose very special challenges for the development of a contemporary architectural ethos. Post- independence India has been subject to a developmental model mainly dependant on centralised economic planning and large scale industrialisation. This has contributed to a rapid growth of urban centres due to a massive influx of migrants from the rural areas.

Today almost a quarter of the country’s large population is located in cities which are ill- equipped in utilities, infrastructure and institutional support necessary to service the very large numbers.

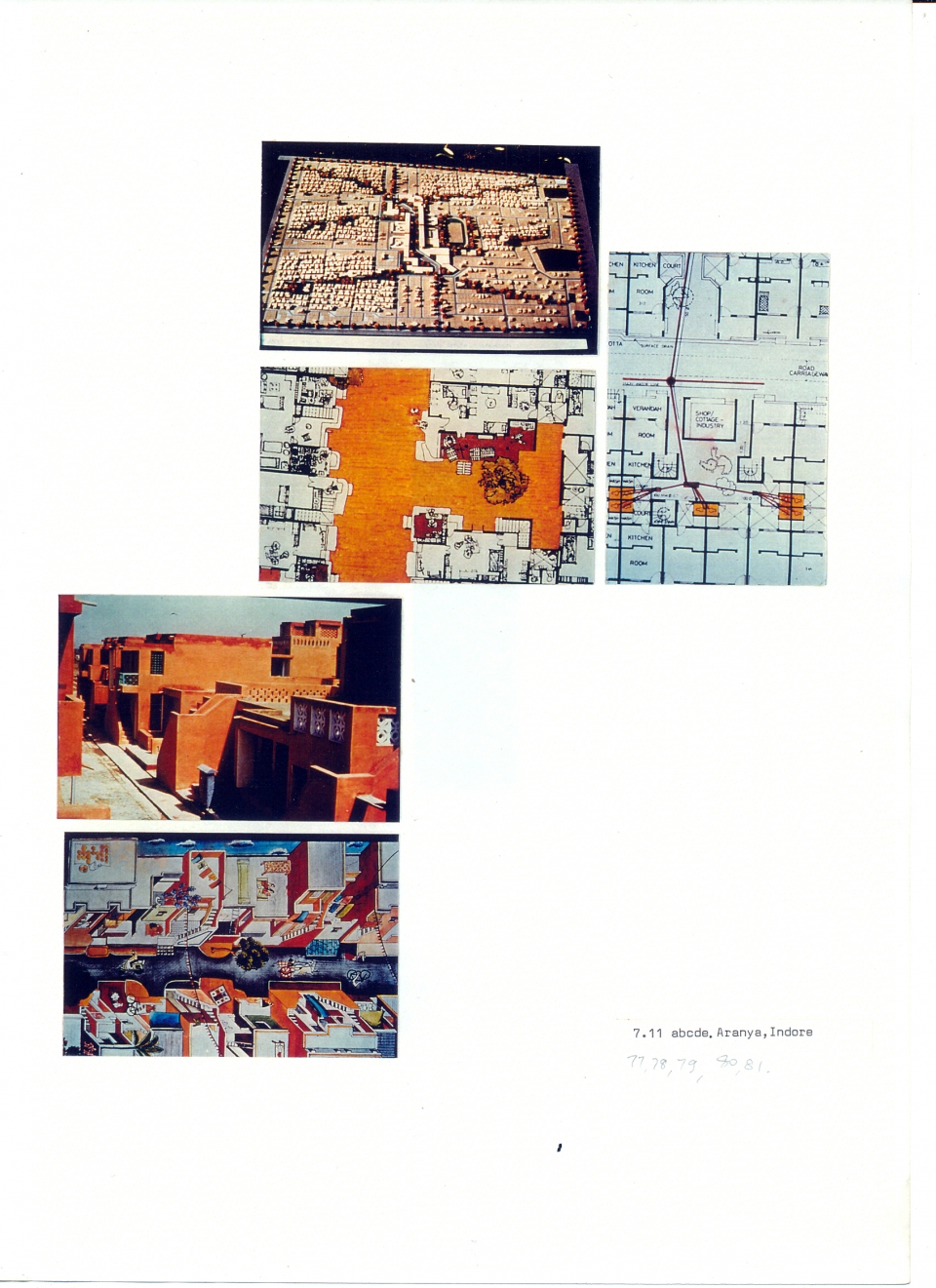

As these expanding cities become home for so many people they undergo transformations to meet the diverse requirements of a great variety of physical, economic, and cultural conditions. While researching into the changing urban phenomena in India, some of us architects, planners and social scientists, have identified 3 distinct types of city which together constitute the urban settlements of today. We have identified these 3 types as:

The organically evolved town, which forms the core of each settlement and often has a historic significance; this type would be exemplified by the residential neighbourhoods of the town of Chanderi in Central India, and by the densely built-up quarters of Shahjahanabad, the old city of Delhi.

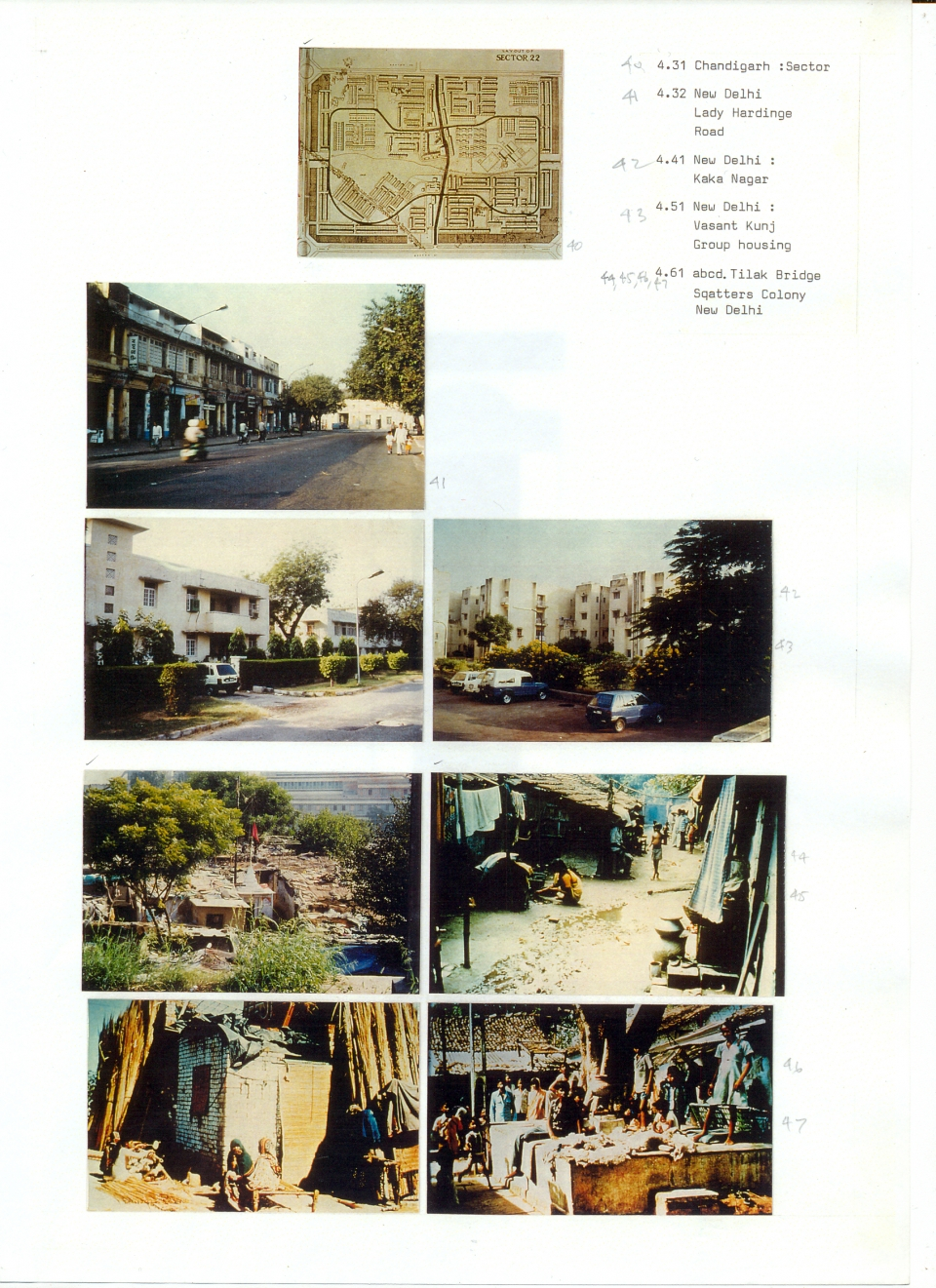

The second type is the planned city, which constitutes the modern extensions laid out according to the designs of town planners, engineers and architects; this can be exemplified by the sector plan of one of the neighbourhoods of the city of Chandigarh, and by some illustrations of parts of New Delhi – a market in a residential neighbourhood of the Imperial zone of New Delhi – a residential area for government officials developed subsequent to the colonial period – a high density housing development by the Delhi Development Authority built for the general public in the last 5 years or so.

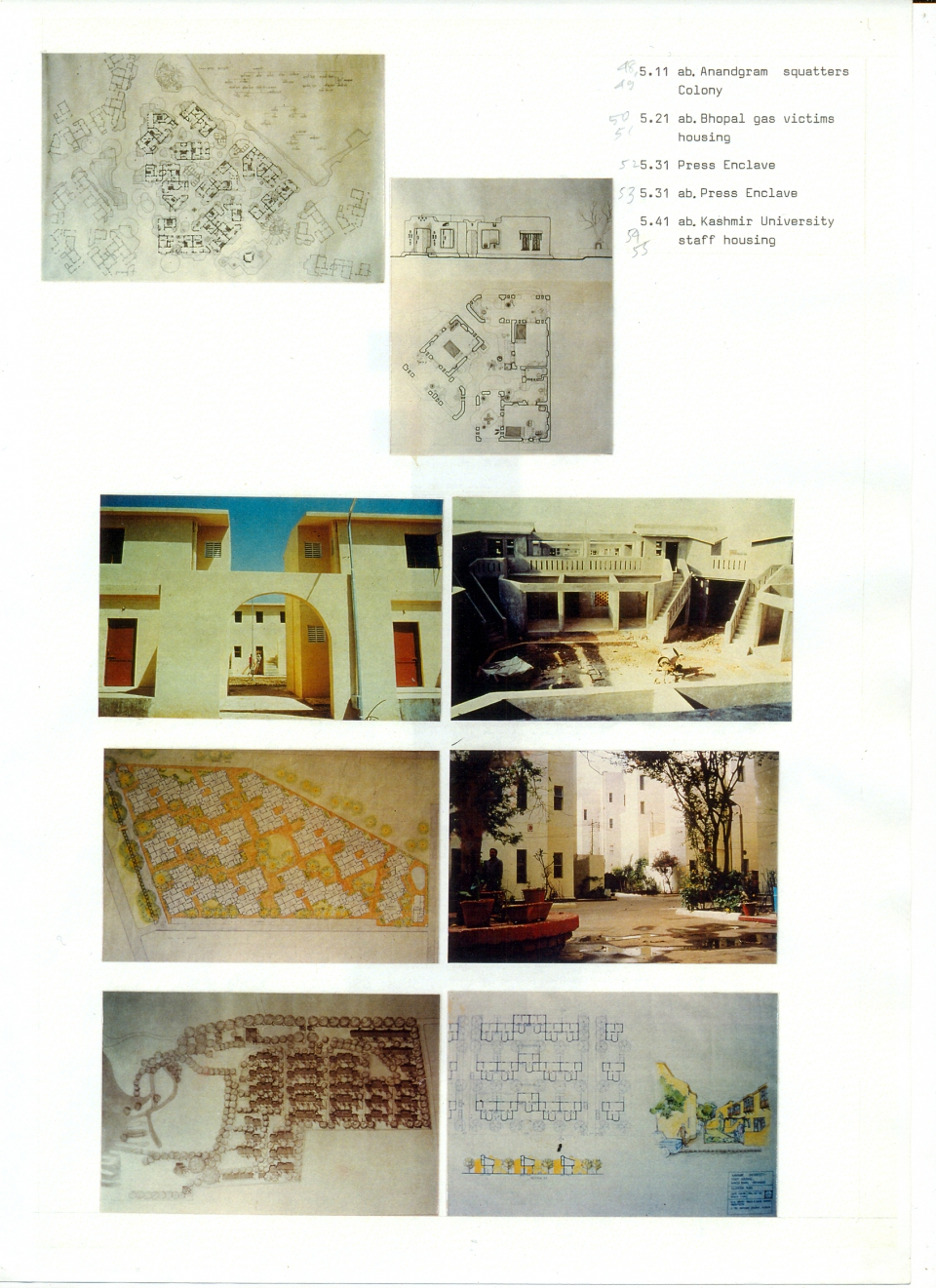

The third urban type is formed by the spontaneous developments generated originally by the very poor migrants, and now increasingly by the more affluent, as colonies which do not have legal sanction of the municipal authorities. These developments emerge on marginal urban lands and in the many twilight zones which are a result of the misfit between the organically evolved and planned parts of the city. Such spontaneous settlements are marked by an almost total lack of urban services, except such as are obtained through piracy, a physical fabric in various stages of temporariness, and to sustain this existence of marginality a social support system which is internally cohensive and grounded in traditional values.

These three urban types, different from each other in terms of their age, physical structure, cultural characteristics, and political rationale, do not easily integrate to form a sustainable whole. Undoubtedly one of the major challenges facing the architects of today is to resolve this variety of built form into a cohesive and harmonious urban structure while respecting the cultural diversity inherent in these existing urban phenomena.

The complexity of human organization and social life is further compounded by the sheer magnitude of the numbers involved. Indian cities are growing at a rate which is quite alarming. Unchecked urban migration combined with inefficient management of resources, and a social system which is not adequately responsive to the scale and pace of technological change, constitutes another great challenge facing planners and architects today.

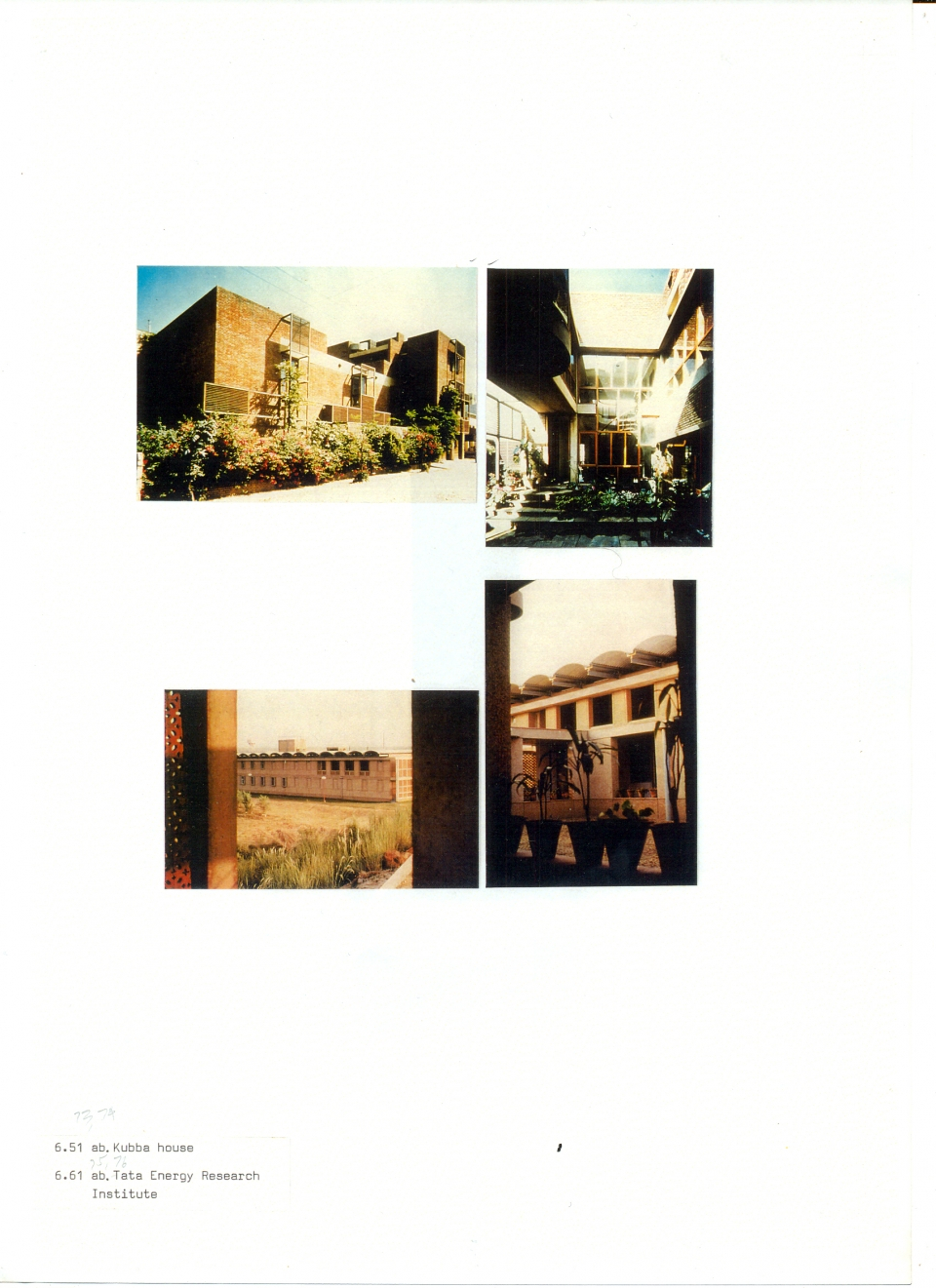

This challenge of very large numbers does, however, have positive implications as well. The requirement of building today, new constructions as well as upgradation of existing structures, is of enormous magnitude. Furthermore, the variety of building types, from the humble homes of the poor, to commercial and institutional projects which embody the complex and pluralistic culture of contemporary Indian life, to the technologically sophisticated industrial structures and plants, is a rich enough mix to inspire a whole generation of architects.